When you walk into a pharmacy with a prescription for a brand-name drug, you might expect the pharmacist to hand you a cheaper generic version-unless the drugmaker has already rigged the system. That’s exactly what’s happening in the U.S. pharmaceutical industry. Companies are using legal loopholes and shady tactics to block generic drugs from reaching patients, even when state laws say they should be allowed. This isn’t just about profits. It’s about patients paying hundreds or thousands more for medicines they need.

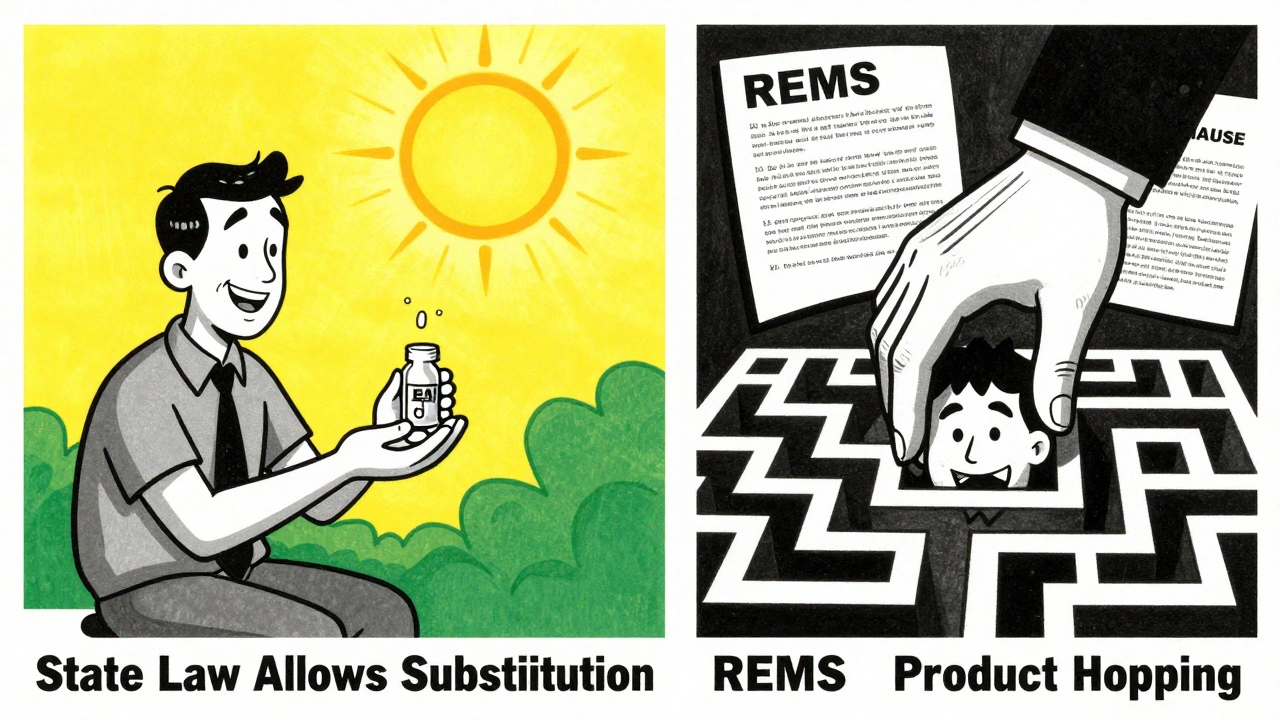

How Generic Substitution Is Supposed to Work

Every state in the U.S. has laws that let pharmacists swap a brand-name drug for a generic version, as long as it’s bioequivalent-meaning it works the same way in the body. These laws exist to save money. Generic drugs cost 80% to 90% less than brand-name versions. When a patent expires, generics should flood the market, and prices should drop fast. In countries like Canada or the UK, that’s exactly what happens. But in the U.S., something gets in the way.The problem isn’t the generics. It’s the brand-name companies. They don’t wait for the patent to expire and then lose market share. Instead, they launch a new version of the drug-slightly different, often with no real medical benefit-and pull the old version off the shelves. This is called product hopping. It’s not innovation. It’s a legal trick to kill competition before it starts.

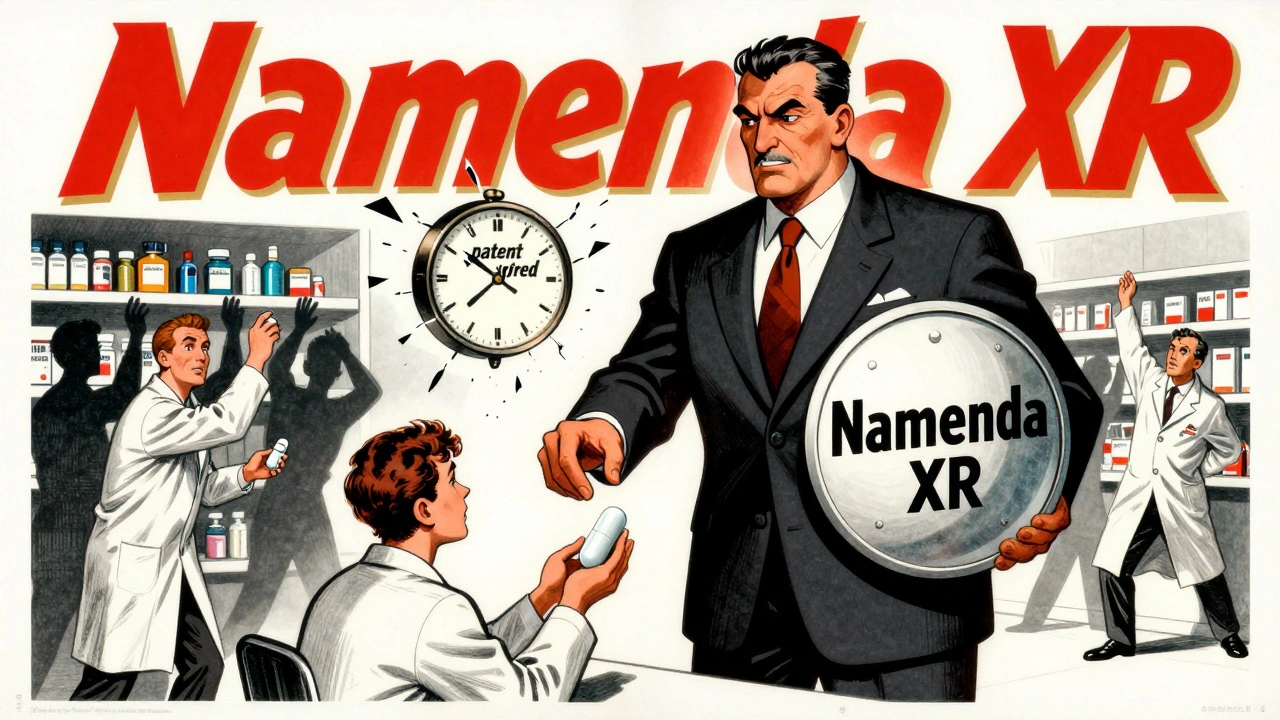

Product Hopping: The Silent Tax on Patients

Take Namenda, a drug for Alzheimer’s. The original version, Namenda IR, was a pill taken twice a day. When its patent was about to expire, the maker, Actavis, introduced Namenda XR-a once-daily extended-release version. Then, 30 days before generics could legally replace Namenda IR, they pulled it from the market. No warning. No transition plan. Just gone.Why does this matter? Because pharmacists can’t substitute generics for Namenda XR unless the original version is still available. State substitution laws only apply to the exact drug listed on the prescription. Once the old version disappears, doctors have to rewrite every prescription for the new one. And most doctors won’t. Patients won’t either. Switching drugs means new side effects, new routines, new co-pays. The transaction cost is too high.

The result? Generic versions of Namenda IR never got a real shot. Patients were forced into Namenda XR, which cost three times more. The Second Circuit Court of Appeals called this out in 2016, ruling it was anticompetitive. But that was the exception, not the rule.

How REMS Abuse Blocks Generic Entry

Another tactic is hiding behind FDA safety programs called REMS-Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies. These were meant to control dangerous drugs, like those with high addiction risk. But brand-name companies have twisted them into weapons.To get FDA approval, generic makers need to test their version against the original drug. That means getting samples. But if the brand refuses to sell them, the generic can’t test, can’t file, can’t enter the market. According to a 2017 study, over 100 generic companies reported being denied samples. One analysis found that for 40 drugs with restricted access, this delay cost the system more than $5 billion a year.

It’s not just about samples. Some companies use REMS to require special training or sign agreements that make it impossible for generics to get access. The FTC calls this a textbook case of monopolization. The brand doesn’t make the drug safer. It just makes sure no one else can sell a cheaper version.

Why Courts Are Split on This

Not every product hop gets blocked. In 2009, a court dismissed a case against AstraZeneca for switching patients from Prilosec to Nexium. Why? Because Prilosec stayed on the market. The court said offering a new version was just competition.But in the Namenda case, the court saw the difference: the original drug was pulled. That’s not competition. That’s sabotage. The FTC’s 2022 report found that courts are inconsistent. Some judges ignore the role of state substitution laws. They think generics can just spend more on ads to win back patients. But that’s not how it works. Generic companies don’t have the budget for national ad campaigns. Their only advantage is price. If they can’t even get on the shelf, they can’t compete.

Then there’s Suboxone. The original tablet version was widely used for opioid addiction treatment. Reckitt Benckiser introduced a film version, then started spreading false claims that the tablets were unsafe. They threatened to pull the tablets from the market. The FTC stepped in. In 2019 and 2020, they forced Reckitt to pay settlements after the court found this was coercion. Patients didn’t choose the film-they were pushed into it.

The Financial Cost to Patients and Taxpayers

This isn’t theoretical. It’s costing billions.Revlimid, a cancer drug, went from $6,000 a month to $24,000 over 20 years. Humira, Keytruda, and Revlimid alone have cost the U.S. system an estimated $167 billion more than they would have in Europe, where generics enter faster. That’s not because Americans need more of these drugs. It’s because the system lets companies delay competition.

When generics are allowed to substitute freely, they take over 80-90% of the market within months. But when product hopping happens, that number drops to 10-20%. In the Ovcon case, a manufacturer introduced a chewable version and then pulled the original. Generic Ovcon sales collapsed. Patients paid more. Insurance paid more. Medicaid paid more.

What’s Being Done About It

The FTC has been pushing back. After the Namenda ruling, they got a court order forcing Actavis to keep selling the old version for 30 days after generics entered. In the Suboxone case, they forced settlements. The Department of Justice has also gone after generic companies-for price-fixing. Teva paid $225 million, the largest criminal antitrust penalty ever for a domestic drug cartel.But enforcement is slow. State attorneys general have stepped in too. New York sued Actavis in 2014 and won an injunction. Other states are watching. The FTC’s 2022 report was a wake-up call. Chair Lina Khan made it clear: product hopping won’t be ignored anymore.

There’s also talk of new laws. Congress is looking at limiting REMS abuse and requiring brands to provide samples to generic makers. Some proposals would let pharmacists substitute generics even if the original drug is withdrawn. That would close the biggest loophole.

What This Means for You

If you’re taking a brand-name drug that’s been on the market for years, check if there’s a generic. If there is, but you’re still getting the expensive version, ask your pharmacist why. If your doctor insists on the brand, ask if there’s a reason beyond cost. Sometimes, it’s just habit.And if you’re on Medicaid, Medicare, or private insurance-you’re paying for this. Every extra dollar spent on a brand-name drug because of product hopping is money taken from your premiums, your taxes, or your out-of-pocket costs.

This isn’t about big pharma being evil. It’s about a system that lets them exploit legal gray areas to protect profits at the expense of patients. The courts are starting to catch on. Regulators are pushing back. But until laws are changed, the game will keep going. And you’ll keep paying the price.

Vivian Amadi

December 10, 2025 AT 16:33This is pure corporate theft. They don't innovate-they sabotage. Pulling a drug off the shelf just to block generics? That's not business. That's extortion. And the courts keep letting them get away with it. Patients are the ones bleeding out while CEOs cash in.

They call it 'product hopping' like it's some clever trick. It's not. It's a felony with a law degree.

Jimmy Kärnfeldt

December 10, 2025 AT 23:11I get why this feels personal. I’ve watched my mom pay $800 for a pill that should’ve cost $80. But here’s the thing-we’re not powerless. States are starting to push back. The FTC’s finally waking up. And patients? We’re talking. Change doesn’t happen overnight, but it’s happening. Keep asking questions. Keep pushing your pharmacist. That’s how the system cracks.

Ariel Nichole

December 12, 2025 AT 17:41This is such an important read. I work in healthcare admin and see this every day. The system’s broken, but it’s not hopeless. Some pharmacies are now pushing back harder on brand-only scripts. And more docs are starting to question why they’re prescribing the expensive version. Small wins, but they add up.

matthew dendle

December 14, 2025 AT 02:23so big pharma is evil? shocker. next u gonna say water is wet or that gravity exists. they make drugs. they wanna make money. what did u expect? they dont give a f*ck about your co pay. get over it. if u cant afford meds go to canada. or better yet, dont get sick.

Lisa Stringfellow

December 14, 2025 AT 16:41I’m tired of these posts. Everyone acts like this is new. It’s been going on for decades. The system’s rigged. Nothing changes. You think Congress cares? You think your vote matters? Wake up. This isn’t a fixable problem-it’s a feature.

Kristi Pope

December 14, 2025 AT 20:59There’s so much pain wrapped up in this. I’ve seen people skip doses because they can’t afford the brand. I’ve seen elders cry because their insurance won’t cover the generic they’ve been on for 10 years. This isn’t just economics-it’s dignity. And the fact that we let this happen? That’s the real tragedy.

But we’re not alone. People are organizing. States are suing. Maybe-just maybe-we’re turning the tide.

Sylvia Frenzel

December 14, 2025 AT 23:58Let’s be real. The U.S. is the only country where this happens. We pay more for drugs than the entire rest of the world combined. And we still act surprised when companies exploit our broken system? We’re the problem. We tolerate it. We don’t demand better. We just pay and shut up.

Paul Dixon

December 16, 2025 AT 06:08Man, I read this and thought about my uncle with MS. He got stuck on this $12k/month drug because the generic got blocked by some sneaky product hop. He didn’t even know it was happening. That’s the scariest part-not the greed, but how invisible it all is.

But hey, at least we’re talking about it now. That’s a start.

Jim Irish

December 17, 2025 AT 02:13The REMS abuse issue is particularly troubling. These programs were designed for patient safety, not corporate protection. When a company uses a safety protocol as a barrier to market entry, it undermines the entire regulatory framework. The FDA must enforce access to reference samples without exception.

It’s not just antitrust-it’s public health.

Mia Kingsley

December 18, 2025 AT 08:29wait so if the drug changes from pill to film its not a generic? thats hilarious. so if i switch from iphone 12 to 13 and someone tries to sell me a cheaper 12 clone its illegal? this whole thing is a joke. people just want free stuff. stop pretending its about health.

Katherine Liu-Bevan

December 19, 2025 AT 13:56One thing missing from most discussions: pharmacists are often legally blocked from substituting even when generics exist, because the brand’s new version isn’t bioequivalent under state law. That’s not a patient choice-it’s a legal trap.

And yes, the FTC’s 2022 report confirmed that 78% of these product hops occur within 60 days of patent expiry. This is calculated. Not accidental. Not innovation. Sabotage.

Also, the Suboxone case? The film wasn’t better. It was just harder to abuse. But the company lied about the tablets being dangerous. That’s fraud. Not competition.

Aman deep

December 19, 2025 AT 20:13Coming from India where generics are everywhere and cheap as chai, this feels surreal. Here, a month’s supply of a drug costs less than a bus ticket. In the U.S., it’s a mortgage payment. I don’t get how we let this happen. People talk about innovation but forget that real innovation helps people-not just profits.

Maybe one day the world will realize: medicine is a right, not a luxury.