DIPF Risk Assessment Tool

Assess Your Risk of Drug-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis

This tool provides general information only. It does not replace medical advice. Consult your healthcare provider for personalized assessment and treatment.

Most people assume that if a drug is approved and prescribed, it’s safe. But some medications quietly scar the lungs over time-often without warning. Drug-induced pulmonary fibrosis (DIPF) is one of those hidden dangers. It doesn’t show up on routine blood tests. It doesn’t always cause immediate symptoms. By the time you notice your breath getting shorter during a walk, or a dry cough that won’t go away, the damage may already be done. And unlike infections or asthma, this scarring doesn’t heal. Once lung tissue turns to fibrous scar, it’s gone for good.

What Exactly Is Drug-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis?

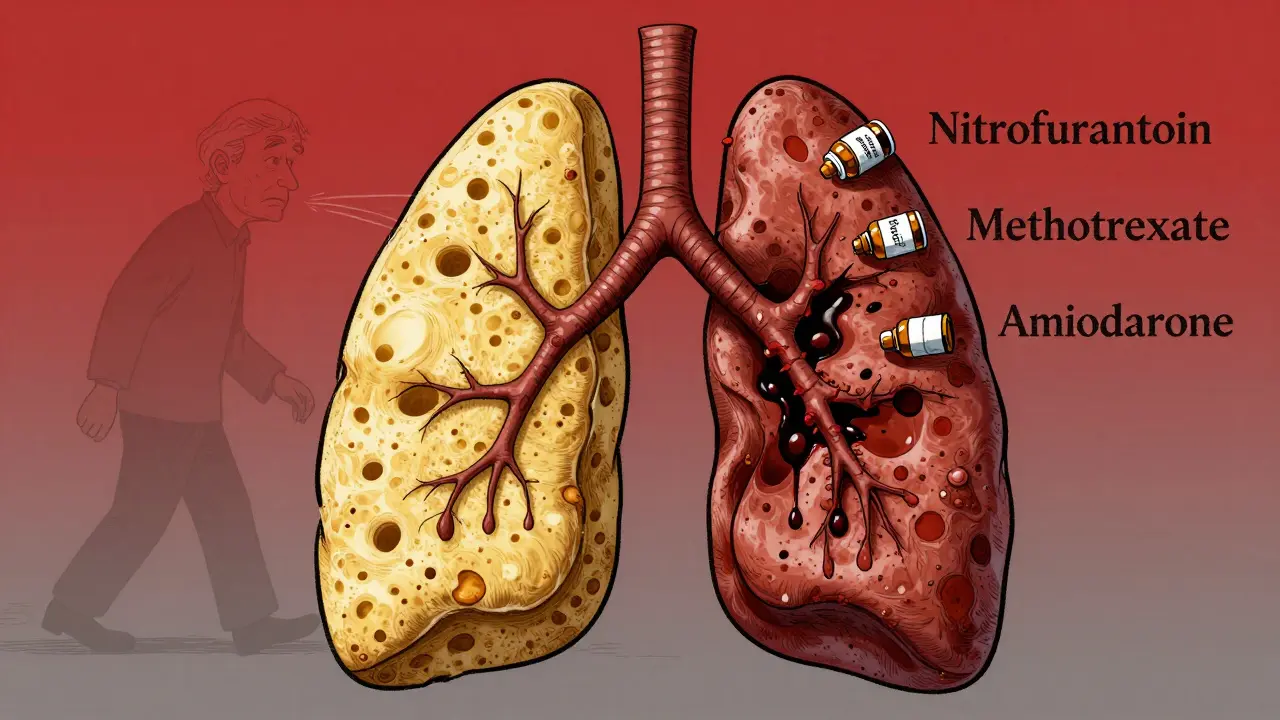

Think of your lungs like a sponge. Tiny air sacs, called alveoli, stretch and contract to pull in oxygen and push out carbon dioxide. In DIPF, those air sacs get inflamed, then slowly replaced by stiff, fibrous scar tissue. This isn’t just inflammation-it’s permanent structural change. The lungs lose their elasticity. They can’t expand properly. Oxygen can’t get into your bloodstream like it should.

It’s not the same as smoking-related lung disease or asbestos exposure. This is caused by drugs. And here’s the kicker: it can happen to anyone, even if they’ve taken the medication for years without issues. One person might use amiodarone for five years and never have a problem. Another might develop fibrosis after just six months. No one knows why. That’s what makes it so dangerous.

The Top 5 Medications That Can Scar Your Lungs

Not all drugs are equal when it comes to lung damage. Some are far more likely to cause trouble. Based on real-world data from New Zealand’s pharmacovigilance system (2014-2024), here are the top offenders:

- Nitrofurantoin - Used for urinary tract infections. Often prescribed long-term for prevention. Risk spikes after 6 months of use. Over 47 cases of lung scarring were reported in New Zealand alone between 2014 and 2024. Elderly patients are most at risk.

- Methotrexate - A common treatment for rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis. About 3-7% of users develop lung inflammation that can turn into fibrosis. Symptoms can appear suddenly: cough, fever, sudden breathlessness. Often mistaken for pneumonia.

- Amiodarone - A heart rhythm drug. Used for decades. Pulmonary toxicity occurs in 5-7% of long-term users. The risk rises sharply after taking over 400 grams total. It builds up in the body, so damage creeps in slowly-sometimes after years.

- Bleomycin - A chemotherapy drug. Up to 20% of patients develop lung damage. It’s one of the most toxic in this category. Doctors monitor lung function closely during treatment, but even then, some cases slip through.

- Cyclophosphamide - Another chemo drug. Used for autoimmune diseases and some cancers. About 3-5% of users develop lung injury. Often overlooked because patients are focused on cancer treatment, not breathing.

These five account for over 40% of all reported cases. But the list keeps growing. New cancer immunotherapies like pembrolizumab and nivolumab, approved since 2011, are now showing up in reports. These drugs boost the immune system to fight cancer-but sometimes, they turn it against the lungs.

Why Does This Happen? The Science Behind the Scarring

It’s not just one mechanism. Different drugs attack the lungs in different ways.

Nitrofurantoin and amiodarone create oxidative stress. They produce harmful free radicals that burn lung cells. Methotrexate triggers an immune overreaction-like an allergic response inside the lungs. Bleomycin directly damages the DNA of lung cells. And newer immunotherapy drugs? They remove the brakes from immune cells, which then attack healthy lung tissue thinking it’s cancer.

There’s no single pattern on X-rays or CT scans. That’s why doctors miss it. A chest scan might show patchy shadows-similar to pneumonia, sarcoidosis, or even aging. Without a detailed drug history, it’s easy to misdiagnose. Many patients are told they’re just getting older. Or that their cough is from allergies. By the time a specialist sees them, months or even years have passed.

How Do You Know If It’s Happening to You?

Early symptoms are subtle. They’re easy to ignore. Here’s what to watch for:

- A dry cough that lasts more than 2 weeks

- Shortness of breath during light activity-like walking to the mailbox or climbing stairs

- Unexplained fatigue or weight loss

- Fever or night sweats without infection

- Joint pain or muscle aches (especially with methotrexate)

One study found that 78% of patients with drug-induced fibrosis had worsening breathlessness. 65% had a chronic cough. 32% had fevers or joint pain. And here’s the scary part: the average time from first symptom to correct diagnosis? 8.2 weeks. That’s over two months of damage piling up.

If you’re on any of these drugs and notice these symptoms, don’t wait. Don’t assume it’s aging. Don’t wait for your next routine checkup. Talk to your doctor now.

What Happens If You Keep Taking the Drug?

The longer you take the drug, the worse the scarring gets. And once scar tissue forms, it’s permanent. Stopping the drug early is the single most effective treatment.

Studies show that 89% of patients improve within three months of stopping the offending medication. But if you wait too long, the damage becomes irreversible. About 15-25% of patients end up with permanent lung function loss-even after stopping the drug.

Some patients need high-dose steroids like prednisone to calm the inflammation. Oxygen therapy is used if blood oxygen drops below 88%. But none of this works if the drug keeps being taken.

And yes, there are deaths. In New Zealand, 30 people died from medication-induced lung damage between 2014 and 2024. That’s a 17.3% mortality rate. Most of those cases were linked to nitrofurantoin, methotrexate, or amiodarone.

How to Protect Yourself

You can’t always avoid these drugs. Sometimes they’re necessary. But you can reduce your risk.

- Ask your doctor: "Is this drug linked to lung damage?" Don’t assume they know. A 2022 survey found only 58% of primary care doctors routinely screen for lung symptoms in patients on high-risk meds.

- Know your baseline: If you’re starting a long-term drug like amiodarone or methotrexate, ask for a pulmonary function test (PFT) before you begin. It’s a simple breathing test. It gives you a benchmark to compare against later.

- Track your symptoms: Keep a log. When did the cough start? When do you feel out of breath? Bring this to your appointments.

- Don’t ignore early signs: A persistent cough isn’t "just a cold." Shortness of breath isn’t "getting older."

- Ask about alternatives: Is there another drug with lower lung risk? For example, some antibiotics other than nitrofurantoin can treat UTIs without the same lung danger.

Regulators are catching on. New Zealand’s Medsafe issued a public warning in December 2024. They now require doctors to inform patients about this risk before prescribing high-risk drugs. But awareness is still low. You have to be your own advocate.

Is There a Cure?

No. There’s no pill that reverses lung scarring. But early action changes everything.

If caught early-within weeks of symptom onset-most patients recover well. Lung function can improve by 60-80% after stopping the drug. Some even return to normal activity levels.

But if you wait six months or more? The chance of full recovery drops sharply. That’s why timing matters more than anything.

Researchers are working on biomarkers-blood tests or genetic markers-that could predict who’s at risk before damage starts. Clinical trials are underway. But for now, vigilance is your best defense.

What Comes Next?

More drugs are being developed every year. Targeted cancer therapies, immune modulators, even new antibiotics-all carry unknown risks. The list of drugs linked to pulmonary fibrosis has grown from 30 in the 1990s to over 50 today. And it’s still climbing.

Healthcare systems are starting to respond. Some hospitals now recommend baseline lung scans before starting amiodarone or methotrexate. But this isn’t standard everywhere. Patients in rural areas, older adults, and those without specialists are still at high risk.

The bottom line? Medications are powerful. They save lives. But they can also harm in ways we don’t always see. If you’re on a long-term prescription, especially for heart, lung, autoimmune, or cancer conditions-know the risks. Ask the questions. Speak up if something feels off.

Your lungs don’t warn you. You have to listen before it’s too late.

Can drug-induced pulmonary fibrosis be reversed?

Yes-if caught early. Stopping the drug immediately is the most important step. In 89% of cases, lung function improves within three months of discontinuation. However, if scarring has already set in, the damage is permanent. The goal is to prevent further injury, not reverse existing scars.

Which drugs are most commonly linked to lung scarring?

Nitrofurantoin, methotrexate, and amiodarone are the top three, based on real-world data from New Zealand and other pharmacovigilance systems. Chemotherapy drugs like bleomycin and cyclophosphamide carry high risk too. Newer immune checkpoint inhibitors (like pembrolizumab) are emerging as significant causes.

How long does it take for lung damage to develop?

It varies. With amiodarone, damage often appears after 6-12 months. Nitrofurantoin can take 6 months to 10 years. Methotrexate may cause sudden lung inflammation within weeks. Bleomycin can trigger damage even after a single dose. There’s no safe timeline-only risk factors.

Are older adults more at risk?

Yes. Most cases occur in people over 60. Older lungs have less reserve, and many long-term medications (like nitrofurantoin for UTIs or amiodarone for arrhythmias) are prescribed to this group. Age alone doesn’t cause it, but it increases vulnerability.

Should I stop my medication if I have a cough?

No-not without consulting your doctor. Stopping a critical drug like amiodarone or methotrexate without medical guidance can be dangerous. But you should report symptoms immediately. Your doctor can evaluate whether the cough is related to the drug, order tests, and decide if it’s safe to switch or stop.

Stephon Devereux

February 13, 2026 AT 02:29It's wild how we treat drugs like magic bullets-pop a pill, problem solved. But lungs? They don't yell. They don't scream. They just... slowly turn to dust. And by the time you notice you're winded climbing stairs, it's already too late. We need systemic change-not just individual vigilance. Doctors should be forced to run baseline PFTs before prescribing amiodarone or nitrofurantoin. Period. No more "I didn't know." This isn't paranoia-it's biology. Your lungs don't regenerate. Once they scar, you're living on borrowed air.

And honestly? The fact that this is still not standard protocol is a moral failure. We screen for everything else-why not this?

steve sunio

February 14, 2026 AT 00:42Ernie Simsek

February 15, 2026 AT 11:11Joanne Tan

February 16, 2026 AT 09:34Reggie McIntyre

February 16, 2026 AT 10:59Carla McKinney

February 17, 2026 AT 12:05Ojus Save

February 17, 2026 AT 12:27Jack Havard

February 17, 2026 AT 15:50