Penicillin Desensitization Eligibility Checker

Question 1: What was your reaction to penicillin?

More than 10% of people in the U.S. say they’re allergic to penicillin. But here’s the truth: about 90% of them aren’t. That’s not a typo. Most of those labels were assigned decades ago after a mild rash or a family history, never confirmed by testing. Yet every time someone with that label gets an infection, doctors reach for stronger, broader antibiotics-drugs that cost more, cause more side effects, and fuel dangerous antibiotic resistance. Penicillin desensitization isn’t a last resort. It’s the smartest way to get the right antibiotic when it’s truly needed.

What Penicillin Desensitization Actually Does

Penicillin desensitization isn’t a cure for allergy. It doesn’t change your immune system permanently. Instead, it’s a controlled, temporary reset. Under close medical supervision, you’re given tiny, increasing doses of penicillin over a few hours. Your body learns to tolerate it-just for that treatment cycle. Once the course ends, the tolerance fades in about three to four weeks. But during that time, you can safely take the full therapeutic dose without a reaction.This matters because penicillin and its cousins (like amoxicillin and ampicillin) are often the most effective, safest, and cheapest antibiotics for serious infections. Think neurosyphilis, endocarditis, or group B strep in pregnancy. Without desensitization, doctors are forced to use drugs like vancomycin, clindamycin, or carbapenems. These aren’t just more expensive-they’re linked to higher rates of C. diff infections, kidney damage, and drug-resistant superbugs.

A 2017 study in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology found that patients mislabeled as penicillin-allergic cost the U.S. healthcare system $3,000 to $5,000 more per hospital stay. That’s not just waste. It’s a public health risk.

Who Can and Can’t Have It

Not everyone is a candidate. Desensitization is only considered when:- Penicillin is the best or only effective treatment

- Alternatives are significantly less effective or more toxic

- The patient has a documented IgE-mediated reaction (hives, swelling, anaphylaxis)

It’s not used if you’ve had:

- Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (SJS)

- Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (TEN)

- Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS)

These are severe, immune-mediated skin reactions that can be fatal. Giving penicillin again-even in small doses-could trigger a deadly recurrence. No exceptions.

Also, if you’ve never had a confirmed reaction-just a label-skin testing should come first. If the skin test is negative, you can often just take a single dose under observation (a graded challenge). Desensitization is reserved for confirmed IgE-mediated allergies where you absolutely need penicillin.

How It’s Done: IV vs. Oral Protocols

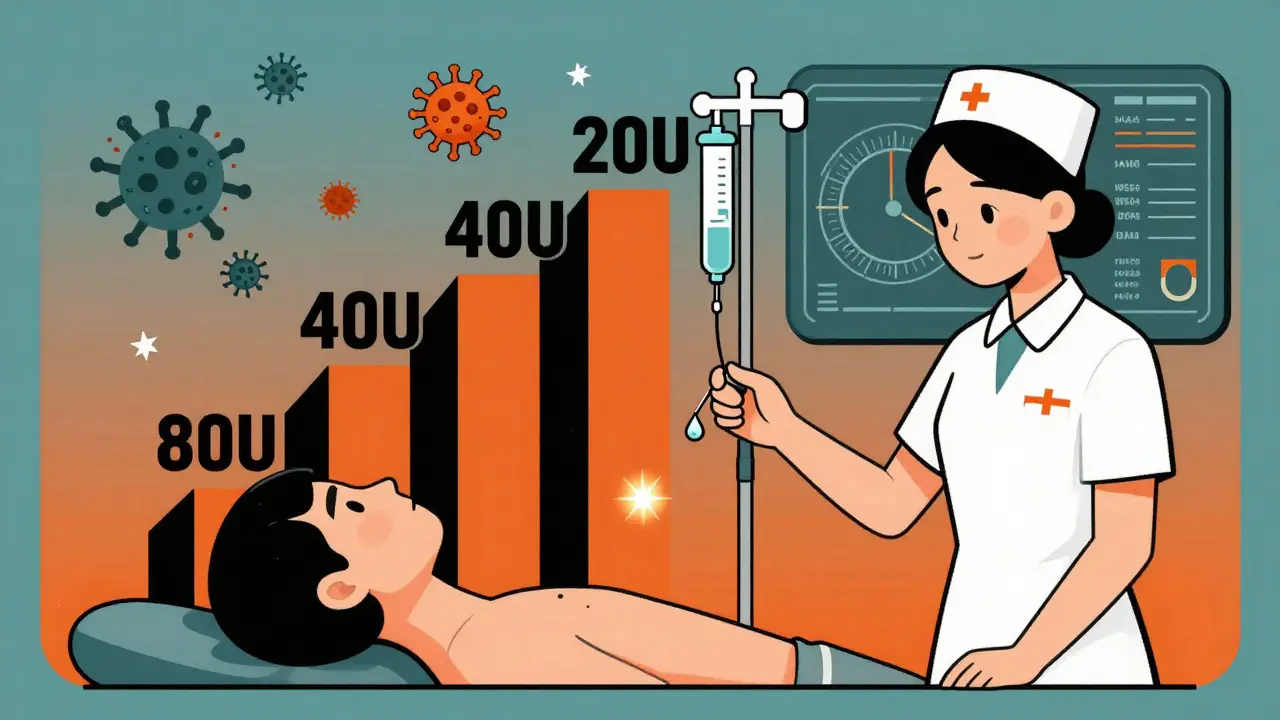

There are two main ways to do it: intravenous (IV) and oral. Both work. But they’re not the same.IV desensitization is faster and more controlled. It’s often used for serious infections like endocarditis or neurosyphilis. The standard protocol starts with a dose so small-20 units of penicillin-that it’s barely detectable. Every 15 to 20 minutes, the dose doubles. By the end of about four hours, you’re receiving the full therapeutic dose. Vital signs are checked every 15 minutes. Nurses watch for anything: a flush, a rash, a drop in blood pressure. If a reaction happens, the dose is paused, antihistamines are given, and the process slows down.

Oral desensitization is slower but often easier. It’s used for less critical infections or when IV access is hard. Doses are given every 45 to 60 minutes. Starting doses are even smaller-sometimes one-millionth of a therapeutic dose. About one-third of patients have mild reactions: itching, a few hives. These are managed with antihistamines and by slowing the schedule. It’s less intense than IV, but it takes longer.

Neither method is proven better than the other in large studies. But experts agree: oral is often safer and more practical. Brigham and Women’s Hospital has successfully done over 170 IV desensitizations. UNC’s protocol notes that oral is ‘easier and likely safer.’

What Happens Before, During, and After

Before the procedure, you’re given premedication. This isn’t optional. It’s standard. You’ll get:- Ranitidine (50mg IV or 150mg by mouth)

- Diphenhydramine (25mg IV or oral)

- Montelukast (10mg oral)

- Cetirizine or loratadine (10mg oral)

All given one hour before the first dose. These reduce the chance and severity of reactions. It’s not a guarantee, but it’s a critical safety net.

During the process, you’re monitored like you’re in the ICU. Blood pressure, heart rate, oxygen levels, and breathing are checked every 15 minutes. An IV line is already set with epinephrine, steroids, and fluids ready to go. Staff are trained in anaphylaxis response. The room is stocked. No shortcuts.

After you’ve reached the full dose, you keep taking penicillin every 4 to 6 hours, on schedule, for the entire treatment course. Skip a dose, and the tolerance can vanish. If you miss a dose by more than a few hours, you may need to restart the entire desensitization process.

Where It’s Done and Who Does It

This isn’t something you do at a walk-in clinic. The CDC and the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (AAAAI) are clear: desensitization must happen in a monitored inpatient setting. That means a hospital. Often, it’s done in Labor and Delivery for pregnant women with syphilis. Why? Because even rare reactions can be dangerous for the baby.Pharmacists prepare the doses with extreme precision-each vial labeled, each concentration checked. Nurses sign off on every single dose. Electronic medical records (EMAR) track every step. One hospital’s protocol requires 19 labels and a 48-hour stop order to prevent accidental reuse.

Only teams with formal training do this. The AAAAI says providers must complete at least five supervised desensitizations before doing one alone. In community hospitals, only 17% have formal protocols. In academic centers, it’s 89%. That gap is dangerous. Patients in small hospitals may be denied this option-or worse, get it done wrong.

Why This Matters Beyond One Patient

Penicillin desensitization isn’t just about helping one person get better. It’s part of a bigger fight: against antimicrobial resistance.The CDC reports that carbapenem-resistant infections jumped 71% between 2017 and 2021. These are infections that don’t respond to most antibiotics. We’re running out of options. When we avoid penicillin because of a mislabeled allergy, we push doctors to use broader-spectrum drugs that destroy good bacteria and leave room for resistant ones to grow.

That’s why the National Action Plan for Health Care-Associated Infections made penicillin allergy delabeling a top priority. The IDSA calls it a ‘high-impact intervention.’ By 2027, they aim for 50% of U.S. hospitals to have formal programs. Right now, it’s just 22%.

There’s progress. New guidelines from Prisma Health in 2024 standardized documentation. The CDC is updating its STI guidelines to expand access in resource-limited areas. Some hospitals are now using electronic health records to automatically flag patients who should be tested-not just labeled.

What Comes Next

The big unanswered question: Can we make the tolerance last longer than three to four weeks? Right now, if you need penicillin again six months later, you have to go through the whole process again. Researchers are studying the immune mechanisms behind desensitization, hoping to find ways to extend the window-or even make it permanent.There’s also talk of expanding this approach to other drugs-like chemotherapy agents (taxanes) and even non-antibiotic beta-lactams. If it works for penicillin, why not others?

But the most urgent step? Stop assuming penicillin allergy. If you’ve been told you’re allergic, ask for a skin test. If you’re a clinician, don’t just accept the label. Push for evaluation. Desensitization isn’t risky because it’s dangerous. It’s risky because it’s underused. And every time we avoid penicillin without testing, we lose ground in the fight against superbugs.

sagar sanadi

January 19, 2026 AT 17:45So let me get this straight - we’re gonna stick people with needles full of penicillin just so we don’t have to use ‘stronger’ antibiotics? 🤔 Next they’ll say we should inject aliens into our veins to cure the flu. 90% aren’t allergic? Bro, I got a cousin who broke out in hives from a single penicillin pill and now he’s ‘allergic’ - and you wanna risk his life for a ‘cost-saving’ scam? 🚨

kumar kc

January 19, 2026 AT 20:19This is why medicine is broken.

clifford hoang

January 20, 2026 AT 12:50Think about it… who benefits from this? 🤔 Big Pharma? The CDC? The hospital systems? 😏 They don’t want you to know penicillin is cheap and effective - they want you hooked on $2,000 IV carbapenems. 🏥💸 And don’t get me started on the ‘premedication’ - ranitidine? That’s the same drug pulled off the market for causing cancer. 😈 You think they’re protecting you? Nah. They’re testing you. 🧪 #ShadowPharma

Jacob Cathro

January 20, 2026 AT 20:55ok but like… why are we even doing this? 🤡 I mean, if 90% of people aren’t actually allergic, why do we even label them in the first place? It’s like putting a ‘gluten-free’ tag on a banana. 🍌 The system is just… broken. And now we’re gonna do a 4-hour IV drip just to give someone amoxicillin? Bro, I’d rather just take the vancomycin and call it a day. 🤷♂️ #lazydoc

Paul Barnes

January 22, 2026 AT 08:36The data presented here is methodologically sound and aligns with current clinical guidelines from the AAAAI and CDC. The economic burden of mislabeled penicillin allergies is well-documented, and the risk-benefit ratio of desensitization in appropriate candidates is overwhelmingly favorable. The procedural safeguards described - including premedication, continuous monitoring, and dose escalation protocols - are not excessive; they are necessary and evidence-based.

pragya mishra

January 23, 2026 AT 12:16Wait, so if I got a rash at 8 years old and never got tested, I’m just… supposed to trust this now? What if I’m one of the 10% who actually *is* allergic? Who’s gonna be responsible when I go into anaphylaxis during this ‘desensitization’? You? The nurse? The hospital? I’m not your guinea pig. 😤

Manoj Kumar Billigunta

January 24, 2026 AT 08:36Hey, I’ve seen this play out in rural India - doctors just say ‘penicillin allergy’ because they don’t have testing kits. But I’ve also seen patients die from C. diff after being given vancomycin for a simple UTI. This isn’t about fear. It’s about access. If your hospital doesn’t do desensitization, ask for a transfer. If they say no, push harder. You’re not being dramatic - you’re being smart. And if you’re a clinician? Start pushing for protocols. It’s not magic. It’s medicine.

Andy Thompson

January 24, 2026 AT 12:49USA is falling behind. In Russia, they just give penicillin and if you react, you get a shot of adrenaline - no 4-hour drip. Why are we overcomplicating this? 🇺🇸💀 We’re so scared of lawsuits we’re killing people with over-treatment. And now they want to make this a ‘national priority’? Bro, just let people take the damn pill. If you’re gonna die from penicillin, you were gonna die anyway. 🤷♂️ #MakeAmericaSafeAgain

thomas wall

January 24, 2026 AT 13:22It is deeply regrettable that the medical profession has allowed such a pervasive and potentially lethal misclassification to persist for decades. The economic argument, while compelling, should not overshadow the fundamental ethical imperative: to do no harm. The very notion of desensitization - a temporary, artificial tolerance - speaks to a systemic failure in diagnostic rigor. One must ask: why was the initial labeling permitted without confirmation? The answer lies not in science, but in complacency.

Arlene Mathison

January 25, 2026 AT 04:46Y’all need to stop being scared of penicillin. I’m 52, got the ‘allergy’ label since I was 6, and I just got desensitized last year for pneumonia. Felt weird, sure - but I didn’t die. And now I’m not paying $1,200 for a 5-day course of clindamycin. 🙌 If you’ve been told you’re allergic - go get tested. It’s not a big deal. You’ll thank yourself later. #StopTheFear

Emily Leigh

January 25, 2026 AT 07:42Okay, so… we’re doing this… because… cost? And… resistance? But… what if… I just… don’t… want… to… be… a… guinea… pig…?? 😭 I mean, seriously - I’m not a lab rat. I’m a human. And if I’m allergic, I’m allergic. No amount of ‘science’ is gonna change that. And now you want me to sit there for 4 hours while they slowly poison me? Like… why??

Carolyn Rose Meszaros

January 26, 2026 AT 03:11I had this done last year after my C-section. I was terrified. 😣 The nurses were amazing - super calm, explained every step. Took 4 hours, felt a little itchy at first, but no big deal. Got my ampicillin, delivered a healthy baby, and didn’t get C. diff. 🤱💖 If you’re nervous - ask for a nurse who’s done it before. It’s not scary if you’re in the right place. #TrustTheProcess

Greg Robertson

January 27, 2026 AT 03:51I just wanted to say - thank you for writing this. My mom had penicillin desensitization for endocarditis last year. She’s fine now. I never knew how much went into it - the labels, the checks, the timing. It’s not just medicine. It’s a whole system of care. People think it’s risky, but honestly? Not doing it is riskier. Just… don’t skip the premed. Seriously. 😊