When you take a pill, injection, or cream, you expect it to work exactly as it should - not weaker, not toxic, not useless. That’s not luck. It’s the result of stability testing, a strict, science-backed process that tells drug makers how long a medicine stays safe and effective under real-world conditions. At the heart of this process are two non-negotiable factors: temperature and time. Get these wrong, and you risk patients getting degraded drugs. Get them right, and you ensure medicines survive heat, humidity, and shelf life without failing.

Why Temperature and Time Matter in Stability Testing

Stability testing isn’t optional. It’s required by law in the U.S., Europe, Canada, Japan, and most other countries. The goal? To prove that a drug doesn’t break down over time. A tablet might look fine after six months, but if its active ingredient has degraded by 15%, it won’t treat your infection. A liquid might look clear, but if proteins have clumped together, it could trigger an allergic reaction. Temperature and humidity accelerate these changes, so testing under controlled conditions lets scientists predict what will happen in your medicine cabinet, warehouse, or delivery truck. The global standard? ICH Q1A(R2). First published in 2003, this guideline came from a collaboration between regulators in the U.S., Europe, and Japan. It’s still the rulebook today. The FDA, EMA, and Health Canada all follow it. No exceptions. And the reason is simple: if a drug passes stability testing under these conditions, it’s approved everywhere. That saves companies millions and ensures patients get consistent, safe products no matter where they live.Long-Term Testing: The Real-World Benchmark

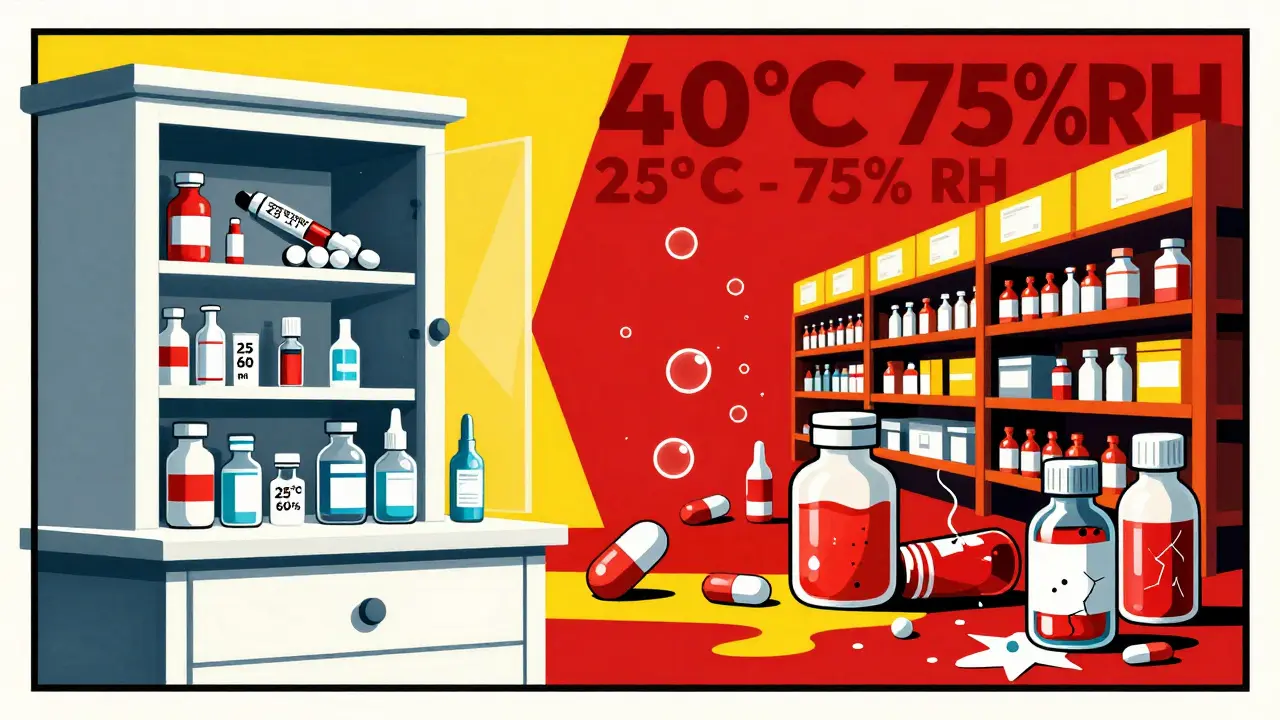

Long-term testing is the gold standard. It’s what you run to determine a drug’s actual shelf life - the date printed on the box. This isn’t a quick test. It’s a marathon. You store the product under conditions that mimic where it will be sold and monitored for months, even years. There are two accepted long-term conditions:- 25°C ± 2°C with 60% RH ± 5% RH

- 30°C ± 2°C with 65% RH ± 5% RH

Accelerated Testing: The Speed Test

No one waits three years to launch a drug. That’s where accelerated testing comes in. This is the high-pressure version. You push the product to its limits to predict how it will behave over years - in just six months. The global rule is simple: 40°C ± 2°C and 75% RH ± 5% RH for six months. This isn’t a guess. It’s based on decades of data showing that this combination roughly mimics 24 months of storage at 25°C/60% RH for most small-molecule drugs. But here’s the catch: it doesn’t work for everything. Hygroscopic drugs - those that soak up moisture - often fail here. Lipid nanoparticles, like those in mRNA vaccines, can break down from freeze-thaw cycles that this test doesn’t capture. Monoclonal antibodies? They’re fragile. A 2021 FDA warning letter to Amgen cited stability failures in a biologic product that degraded under standard accelerated conditions, even though it passed at lower temperatures. So while 40°C/75% RH is the rule, smart companies run extra tests. If your drug is sensitive, you might test at 30°C, 35°C, or even 50°C to see how it behaves under stress.

Refrigerated Products: Cold Isn’t Always Safe

Not all drugs are kept at room temperature. Insulin, many vaccines, and biologics need refrigeration. For these, the rules change. Long-term testing is done at 5°C ± 3°C for at least 12 months. But here’s the twist: accelerated testing for refrigerated products isn’t at 40°C. That would melt them. Instead, it’s done at 25°C ± 2°C with 60% RH ± 5% RH - the same as long-term for room-temperature drugs. You’re not stressing the product with heat. You’re stressing it with time at a warmer-than-intended temperature. This is critical. A vaccine stored at 10°C for a week might seem fine, but if it’s exposed to that temperature repeatedly during transport, the active ingredient can degrade. That’s why companies track temperature logs during shipping. One 2021 recall by Teva Pharmaceuticals happened because their generic insulin product showed aggregation at 25°C - something their original stability protocol didn’t catch.Global Zones and Climate Differences

The world isn’t one climate. ICH recognizes five zones:- Zone I: Temperate - 21°C / 45% RH

- Zone II: Mediterranean/Subtropical - 25°C / 60% RH

- Zone III: Hot-Dry - 30°C / 35% RH

- Zone IVa: Hot-Humid/Tropical - 30°C / 65% RH

- Zone IVb: Hot/Higher Humidity - 30°C / 75% RH

What Counts as a ‘Significant Change’?

ICH Q1A(R2) doesn’t define “significant change” with numbers. That’s a problem. It says it’s a change in appearance, content, impurities, or dissolution that makes the product unfit. But what’s “significant”? Is a 3% drop in potency a failure? What about a 0.5% increase in a toxic impurity? In practice, companies set their own thresholds - often 5% for potency, 0.1% for impurities. But regulators don’t always agree. A Pfizer quality analyst shared on Reddit that a 4.8% assay drop triggered a regulatory rejection, even though it was statistically insignificant. The regulator said: “It’s outside specification. That’s a failure.” No discussion. No flexibility. That subjectivity causes delays, retests, and sometimes recalls.

henry mateo

December 30, 2025 AT 19:51man i just took my blood pressure med this morning and never thought about how long it actually lasts or if it's still good. this post blew my mind. thanks for laying it out like this.

Glendon Cone

December 31, 2025 AT 00:43👏 solid breakdown. i work in logistics for pharma and we’ve had *so* many near-misses with temp excursions. one time a shipment got stuck in a warehouse in Mexico for 3 days at 42°C. we had to scrap 20k vials. no one wants to be the guy who let insulin turn to soup.

Aayush Khandelwal

January 1, 2026 AT 20:20the ICH Q1A(R2) is basically the bible for stability, but let’s be real - it’s a 20-year-old document written for aspirin and amoxicillin. now we got mRNA vaccines that need to be shipped in dry ice and biologics that cry if you look at them wrong. we’re using a hammer to assemble a quantum computer. Q1F can’t come soon enough.

also, ‘significant change’ being undefined? that’s regulatory whack-a-mole. one lab’s 4.9% drop is another’s ‘minor fluctuation.’ no wonder companies go bankrupt just trying to get approvals.

Kunal Karakoti

January 2, 2026 AT 04:23it’s fascinating how something so technical - temperature and humidity - ends up being the difference between life and death. we treat medicine like it’s magic, but it’s just chemistry, carefully guarded by data. maybe we should teach this in high school. not just how to take pills, but why they don’t turn toxic.

Joseph Corry

January 4, 2026 AT 03:47oh wow, another post pretending regulatory compliance is some noble, sacred ritual. let me guess - you also think the FDA is a saint and big pharma is just trying to ‘save lives.’ please. stability testing is a $20B compliance theater. companies game the system with accelerated models they never validate. regulators look the other way until there’s a recall. then they blame the ‘laboratory error.’

the real problem? profit margins. if a drug expires in 12 months instead of 36, you sell 3x as much. that’s not science. that’s capitalism.

Colin L

January 4, 2026 AT 19:15you know what really gets me? the humidity control. i used to work in a lab in Manchester where the air was so damp, the walls sweated. we had these chambers that were supposed to hold 60% RH, but every time it rained, the whole system would go haywire. we’d get 72% for three days straight. we didn’t report it because we knew they’d make us restart the whole 12-month study. so we just… adjusted the data. quietly. everyone does. it’s not unethical - it’s survival. the system is broken, not us.

and don’t even get me started on the paperwork. i spent 14 hours last week filling out forms for a single vial’s temperature log. no one reads it. not even the auditors. it’s all performative. we’re all actors in a play where the script was written in 2003.

Hayley Ash

January 4, 2026 AT 20:39so let me get this straight - you’re telling me a drug can be perfectly fine in Europe but turn into poison in India because of humidity? wow. so the real problem isn’t the science. it’s that rich countries get better medicine because they can afford better storage. and we’re supposed to be impressed by ‘global standards’? lol. the world is a pyramid scheme with pills at the bottom

kelly tracy

January 5, 2026 AT 13:55you’re all so naive. if you think this is about patient safety, you’ve never worked in pharma. stability testing exists to protect companies from lawsuits, not people from dying. they test to the minimum. they don’t test for what happens when a grandma leaves her insulin in a hot car for 3 hours. they test for what happens in a perfectly controlled warehouse. and then they charge $500 for a 30-day supply. this isn’t science. it’s a scam dressed in lab coats.

srishti Jain

January 7, 2026 AT 04:30lol at people acting like this is new info. every pharmacist in India knows this. we’ve been seeing expired meds in rural clinics for decades. no one cares until it’s a rich kid in Boston who gets sick.

Shae Chapman

January 7, 2026 AT 16:35thank you for writing this. i’m a nurse and i see the aftermath of bad storage all the time - patients with rashes, fevers, no improvement. we never know if it’s the drug or the storage. this post gave me words to explain it to my patients. 🙏

Sandeep Mishra

January 8, 2026 AT 01:07really appreciate this. as someone who grew up in a village where medicines were stored on rooftops during summer, i’ve seen what happens when temp control isn’t a priority. it’s not just about data - it’s about dignity. everyone deserves a pill that works, no matter where they live. maybe we need a global ‘stability equity’ fund - not just for testing, but for shipping, refrigeration, and training local pharmacists. this isn’t just science. it’s justice.

Cheyenne Sims

January 8, 2026 AT 18:35the fact that the FDA accepts 6-month data for filing is a national security risk. The United States of America does not compromise on public health standards. If Europe wants to play fast and loose with drug safety, that’s their problem. But we must uphold the highest standard - 12 months minimum, full data, zero exceptions. Anything less is an insult to American patients.