When you’re taking nilotinib for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), your main focus is keeping the disease under control. But over time, some patients start hearing whispers about a different kind of risk: second cancers. It’s not something doctors always bring up upfront, but it’s real-and it’s something you should understand clearly.

What is nilotinib, and why is it used?

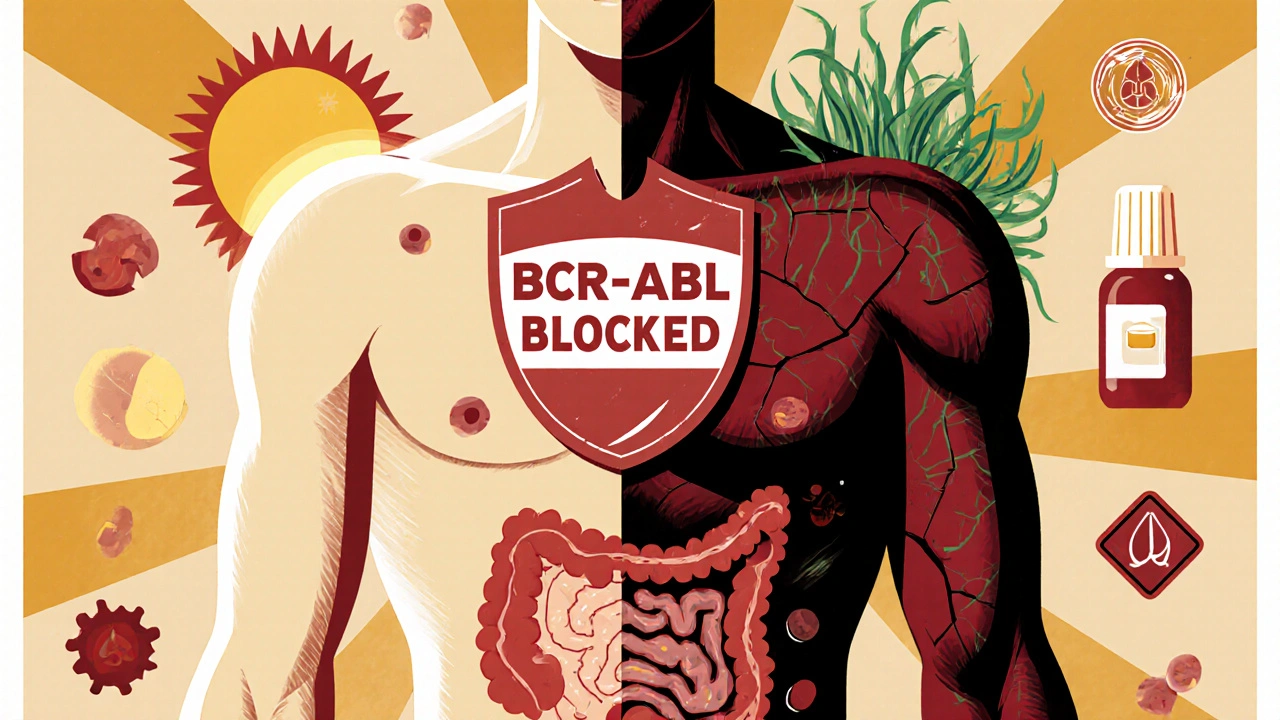

Nilotinib is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), a type of targeted therapy designed to block the abnormal protein that drives chronic myeloid leukemia. That protein, called BCR-ABL, is the reason CML cells multiply out of control. Nilotinib shuts that signal down, often bringing the disease into deep remission. It’s not a cure, but for many, it turns CML into a manageable condition-like diabetes or high blood pressure.

First approved by the FDA in 2007, nilotinib became a go-to option for patients who didn’t respond to imatinib, the first-generation TKI. Today, it’s still widely used, especially in early-stage CML. Studies show that over 80% of patients starting nilotinib achieve a major molecular response within two years. That’s powerful. But every drug has trade-offs, and one of the most serious involves cancer risk.

What are second cancers, and how are they linked to nilotinib?

A second cancer isn’t a return of your original leukemia. It’s a completely new, unrelated cancer that develops later-sometimes years after you started treatment. These can include skin cancer, colon cancer, lung cancer, or even blood cancers like acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

The link between nilotinib and second cancers isn’t random. Clinical trials and long-term follow-up studies have shown a small but measurable increase in certain cancers among patients taking nilotinib compared to those on older drugs like imatinib. One large study published in Blood in 2020 followed over 1,200 CML patients for five years. Those on nilotinib had a 2.5 times higher rate of non-melanoma skin cancers and a slightly elevated risk of colorectal cancer.

Why does this happen? The exact mechanism isn’t fully understood. But researchers believe nilotinib may interfere with DNA repair pathways in healthy cells. Over time, that damage can accumulate and lead to mutations that trigger cancer. It’s not that nilotinib causes cancer directly-it’s more like it quietly lowers your body’s defenses against it.

Who’s most at risk?

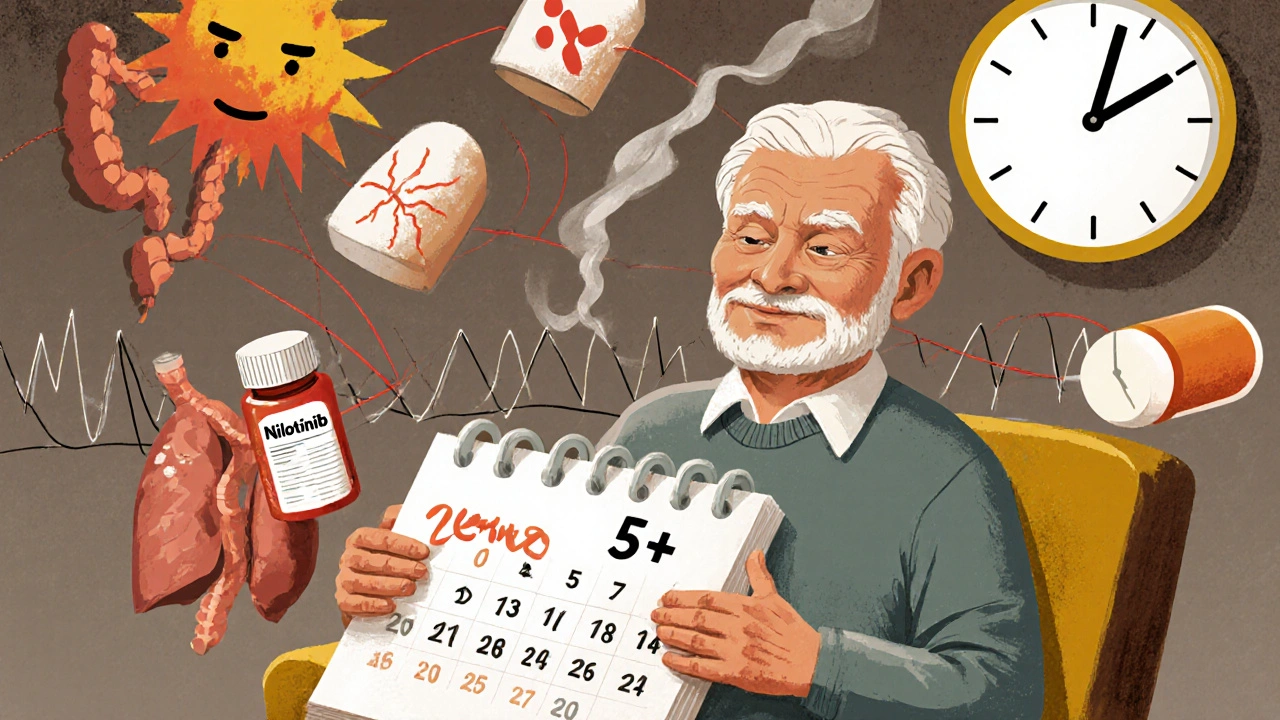

Not everyone taking nilotinib will develop a second cancer. But some people face higher odds.

- Older patients: Risk increases after age 60. Aging cells already have more DNA damage; adding a drug that affects repair makes it worse.

- Long-term users: The longer you’re on nilotinib-especially beyond five years-the more your risk climbs.

- Those with prior radiation or chemotherapy: If you had treatment for another cancer before CML, your body’s repair systems are already stressed.

- Smokers and heavy drinkers: These habits add their own cancer-causing damage on top of what nilotinib might do.

One study from the European LeukemiaNet found that patients over 65 on nilotinib for more than six years had a 12% cumulative risk of developing a second cancer. That’s not high, but it’s enough to warrant attention.

What types of second cancers are most common?

Based on data from over 5,000 patients tracked since 2010, the most frequently reported second cancers linked to nilotinib include:

- Non-melanoma skin cancers: Basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. These are the most common-often appearing on the face, neck, or hands. They’re usually treatable if caught early.

- Colorectal cancer: A small but consistent rise in incidence, especially in patients over 55.

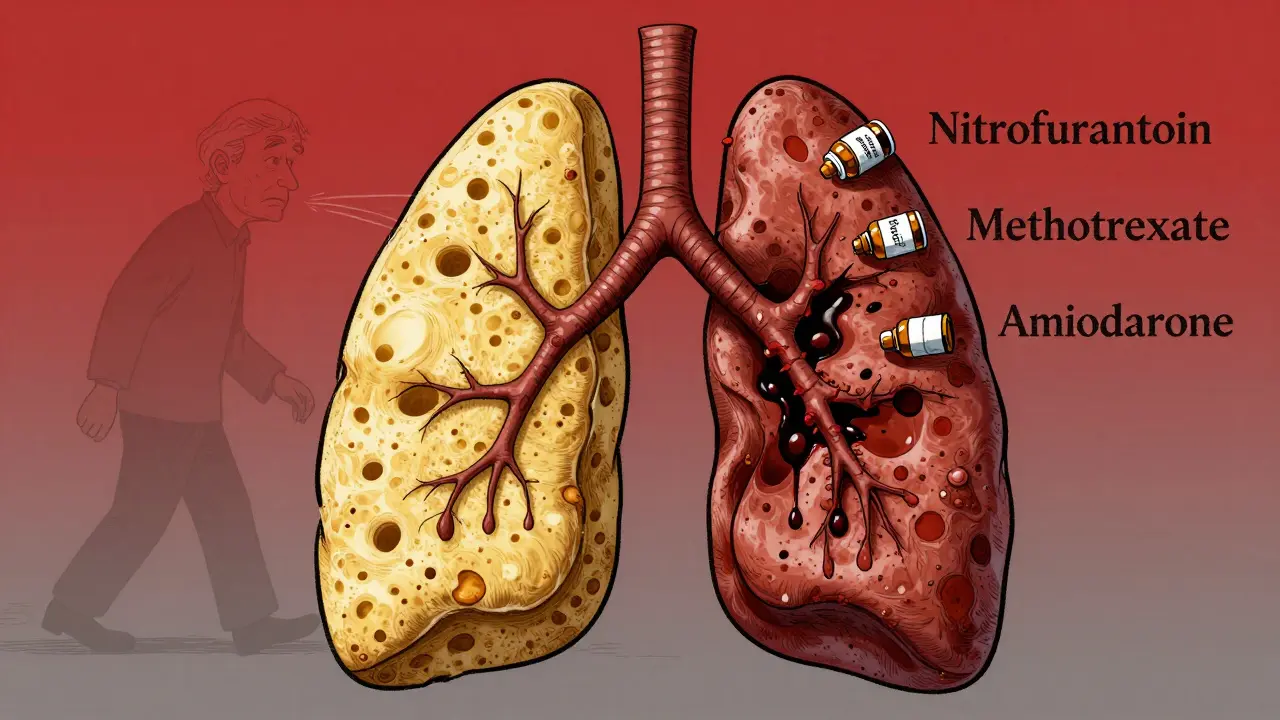

- Lung cancer: Seen more often in smokers on long-term nilotinib.

- Bladder cancer: A few case reports, but the link is still being studied.

- Acute myeloid leukemia (AML): Rare, but when it happens, it’s aggressive. It’s not a relapse of CML-it’s a new, unrelated leukemia.

Importantly, melanoma and lymphoma rates haven’t increased significantly with nilotinib use. That’s reassuring.

How do doctors monitor for second cancers?

If you’re on nilotinib, your care team should be watching-not just for CML response, but for signs of other cancers. Routine checks include:

- Annual skin exams: A dermatologist should check your skin from head to toe. Don’t skip this-even if you think you’re not at risk.

- Colonoscopies: Starting at age 50 (or earlier if you have family history). Every 5 years, or as advised.

- Lung cancer screening: For current or former smokers, low-dose CT scans are recommended annually after age 50.

- Blood tests: While not specific for second cancers, unusual drops in blood counts or new abnormalities can signal trouble.

Some oncologists now recommend baseline imaging (like a full-body MRI or CT) before starting long-term TKI therapy, especially for patients over 55. It’s not standard everywhere, but it’s becoming more common in major cancer centers.

Can you reduce your risk?

Yes. You’re not powerless. Here’s what actually works:

- Sun protection: Wear broad-spectrum sunscreen daily. Use hats and long sleeves. UV exposure is the #1 trigger for skin cancers, and nilotinib makes your skin more vulnerable.

- Quit smoking: If you smoke, stopping now cuts your risk of lung cancer and many others. It’s the single most effective thing you can do.

- Limit alcohol: Even moderate drinking increases colorectal and liver cancer risk. Stick to one drink a day-or better, none.

- Healthy diet: Eat more fiber, vegetables, and whole grains. Reduce processed meats. These habits lower colorectal cancer risk, which matters if you’re on long-term nilotinib.

- Stay active: Regular exercise reduces inflammation and supports immune function. Aim for 150 minutes a week.

There’s no magic supplement or vitamin that blocks nilotinib-related cancer risk. Don’t waste money on unproven “cancer-prevention” products. Stick to evidence-based habits.

Should you switch medications?

This is the big question. If you’re doing well on nilotinib-with deep molecular remission and no side effects-switching might do more harm than good. CML can flare back if you change drugs too soon.

But if you’re over 60, have a family history of colon or skin cancer, or you’ve been on nilotinib for more than five years, it’s worth talking to your oncologist about alternatives. Drugs like bosutinib or ponatinib may have different risk profiles. In some cases, switching to interferon or even stopping TKI therapy under strict monitoring (treatment-free remission) could be an option.

Never stop or change your medication on your own. But do ask: “Based on my age, history, and how long I’ve been on this drug, is there a safer option?”

What does the future hold?

Research is moving fast. Newer TKIs like asciminib (approved in 2021) are designed to target BCR-ABL in a different way-without interfering with DNA repair pathways. Early data suggest a lower risk of second cancers. If you’re newly diagnosed, you might start on one of these newer drugs instead.

Also, scientists are testing blood tests that can detect early signs of DNA damage in healthy cells. In the next few years, we may have a way to predict who’s at highest risk before cancer even develops. That could mean personalized monitoring plans-some people get frequent scans, others don’t need them at all.

For now, the message is simple: stay informed, stay vigilant, and stay in touch with your care team. Nilotinib saved your life once. Don’t let fear stop you from using it-but don’t ignore the risks either.

Does nilotinib cause leukemia to come back?

No, nilotinib doesn’t cause CML to return. In fact, it’s one of the most effective drugs at keeping it under control. What it may increase is the risk of a completely new, unrelated cancer-not a relapse of your original leukemia.

How common are second cancers in patients taking nilotinib?

About 5% to 10% of patients on long-term nilotinib (five or more years) develop a second cancer. That’s higher than the general population, but still a minority. The risk rises with age and duration of treatment.

Are skin cancers from nilotinib dangerous?

Most are not. Non-melanoma skin cancers like basal cell carcinoma are highly treatable when caught early. They rarely spread. But melanoma-though rare-is aggressive. That’s why regular skin checks are critical.

Can I take supplements to lower my cancer risk?

No supplement has been proven to reduce nilotinib-related cancer risk. Antioxidants like vitamin C or E may even interfere with how nilotinib works. Stick to food-based nutrition, sun protection, and avoiding tobacco. Those are the only proven tools.

Should I stop taking nilotinib if I’m worried about cancer?

Never stop without talking to your doctor. Stopping nilotinib suddenly can cause CML to return aggressively. If you’re concerned, ask about switching to a different TKI or entering a treatment-free remission program under close monitoring.

Craig Venn

November 1, 2025 AT 01:40Nilotinib’s DNA repair interference is well-documented in the literature but often undercommunicated to patients. The 2020 Blood study showed a clear signal for non-melanoma skin cancers and colorectal risk, especially beyond 5 years. Monitoring isn’t optional-it’s baseline care. Skin exams every 6 months, colonoscopies starting at 45 if you’re on long-term TKI, and low-dose CT for smokers. No fluff. Just science.

Sarah Major

November 1, 2025 AT 10:40I’ve been on nilotinib for seven years and never once had my doctor mention second cancers until I read this post. Now I’m terrified. I’ve had three basal cell carcinomas removed. They called it ‘sun damage.’ But now I wonder-was it the drug all along? I feel like I was lied to.

Amber Walker

November 2, 2025 AT 10:10STOP PANICKING. I’m 52 and on nilotinib since 2018. I’ve had one tiny skin cancer removed. I wear sunscreen every day. I quit smoking. I eat kale. I’m alive. And I’m not dying of CML. You can’t control everything-but you can control sunscreen and your damn diet. Don’t let fear steal your life.

Nate Barker

November 2, 2025 AT 16:56Big Pharma knows this. They don’t tell you because they make billions off lifelong TKIs. They’d rather you die of skin cancer than lose a customer. The real story? Nilotinib is a slow poison wrapped in a miracle drug label. And your oncologist? They’re paid to keep you on it. Ask them about asciminib. They’ll dodge.

charmaine bull

November 3, 2025 AT 22:01Thank you for this. I’ve been on nilotinib for 4 years and just had my first colonoscopy. No polyps. But now I’m scheduling my first full-body dermatology check. I’ve been avoiding it because I didn’t want to think about it. But this post made me realize: awareness isn’t fear. It’s power.

Torrlow Lebleu

November 4, 2025 AT 22:29Everyone’s acting like this is news. The FDA’s own data shows a 2.4x increase in non-melanoma skin cancers. It’s in the prescribing info. You just didn’t read it. And now you’re mad at your doctor? You’re the adult here. Do your homework. Or stop complaining.

Christine Mae Raquid

November 5, 2025 AT 07:16I cried after reading this. My mom died of colon cancer. Now I’m on nilotinib and they didn’t even warn me? I feel like I’m being used as a guinea pig. What if I get it too? What if I leave my kids without a mom? This isn’t just medicine-it’s a gamble with my family’s future.

Sue Ausderau

November 5, 2025 AT 16:39There’s a quiet dignity in managing risk without panic. Nilotinib gave me back my life. Now I’m learning to protect it-not by avoiding the drug, but by honoring my body’s limits. Sunscreen. Sleep. Walks. No sugar. I don’t need a miracle. I just need to be consistent. And I am.

Tina Standar Ylläsjärvi

November 6, 2025 AT 10:01My oncologist just switched me to asciminib last month. I was on nilotinib for 6 years. Had two basal cell cancers. No AML. No colon issues. But the skin stuff kept happening. Asciminib’s early data looks way cleaner. If you’re past 5 years on nilotinib and have any risk factors-ask about it. Don’t wait for them to bring it up.

M. Kyle Moseby

November 6, 2025 AT 16:05You’re all overreacting. If you don’t smoke and wear sunscreen, you’re fine. This isn’t rocket science. Stop reading scary stuff online and just do what your doctor says.

Zach Harrison

November 7, 2025 AT 09:50Thanks for the post. I’m 58, on nilotinib since 2016. Had a colonoscopy last year-clean. Skin checks every 6 months-no new lesions. I don’t drink, I walk 5 miles a day, and I wear SPF 50 every day, rain or shine. This isn’t about fear. It’s about being smart. You can live a full life on this drug. Just don’t sleepwalk through it.