TNF Inhibitor TB Reactivation Risk Calculator

Patient Risk Assessment

This tool estimates your risk of tuberculosis reactivation when starting TNF inhibitor therapy based on clinical factors.

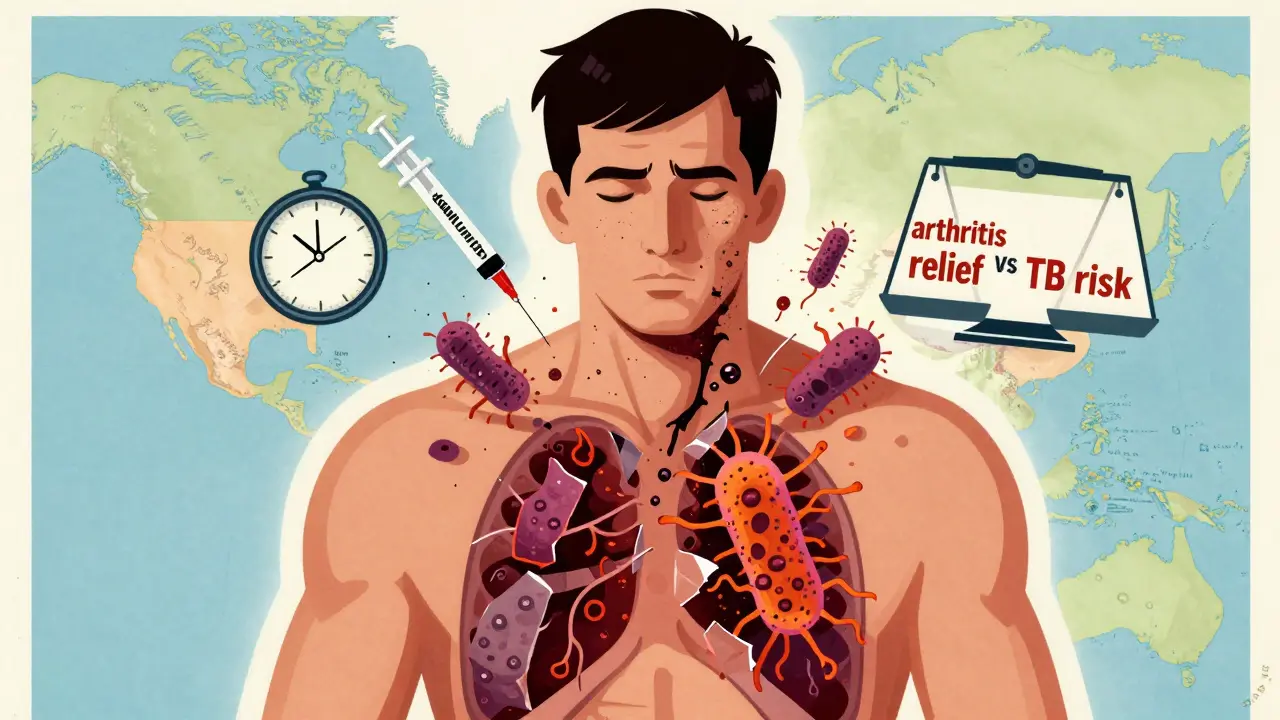

When you start a TNF inhibitor for rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, or Crohn’s disease, you’re getting powerful relief from inflammation. But there’s a quiet danger hiding in the background: TNF inhibitors can wake up dormant tuberculosis. It’s not a common event, but when it happens, it’s often serious - and sometimes deadly. The good news? This risk is predictable, preventable, and manageable - if you know exactly what to look for and when to act.

Why TNF Inhibitors Raise TB Risk

Your body keeps tuberculosis in check with tiny immune structures called granulomas. These are like biological prisons for the TB bacteria, holding them in place so they can’t spread. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) is the glue that holds these granulomas together. When you take a TNF inhibitor, you’re turning off that glue. Without it, the granulomas fall apart, and the bacteria escape. Not all TNF inhibitors are the same. There are two main types: soluble receptor blockers like etanercept, and monoclonal antibodies like infliximab and adalimumab. The antibody drugs bind tightly to both free-floating and membrane-bound TNF. That’s the problem. Membrane-bound TNF is what keeps granulomas intact. Etanercept only blocks the free-floating kind, so it leaves the granuloma structure mostly untouched. That’s why studies show patients on infliximab or adalimumab are more than three times as likely to reactivate TB as those on etanercept.Who’s at Risk - And Where

Your risk isn’t just about the drug you take. It’s also about where you’re from. In Australia, the U.S., or Canada, TB is rare - about 2 to 5 cases per 100,000 people. But in countries like India, the Philippines, Nigeria, or Vietnam, it’s common. If you or your family came from one of those places, you’re far more likely to carry latent TB without knowing it. Even if you’ve lived in a low-risk country for decades, past exposure can still matter. A 2024 study of 519 patients on TNF blockers found that 1.3% developed active TB - and half of them had no history of TB exposure. That means screening isn’t just for immigrants. It’s for everyone.Screening: What Tests Actually Work

Before starting any TNF inhibitor, you need two things: a test and a conversation. The two standard tests are the tuberculin skin test (TST) and the interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA). TST is cheaper and widely available. IGRA is more accurate, especially if you’ve had the BCG vaccine (common in many countries). But here’s the catch: neither test is perfect. About 18% of people who later develop TB had negative results before treatment. That’s why guidelines now recommend a two-step approach for high-risk patients: start with IGRA. If it’s negative, follow up with TST. In places with limited resources, TST alone is still used - but you need to know its limits. A negative test doesn’t mean zero risk. In 2023, the Infectious Diseases Society of America updated its guidelines to say: if you’re from a high-TB-burden country (over 40 cases per 100,000), treat for latent TB even if your test is negative. That’s because the tests can miss up to 30% of infections in these populations.

Treating Latent TB Before Starting Therapy

If your test is positive, you don’t start the TNF inhibitor right away. You treat the latent infection first. The old standard was nine months of isoniazid. But that’s hard to stick with. Side effects like liver damage cause nearly a third of patients to quit. Now there are better options. A four-month course of rifampin and isoniazid, approved by the FDA in 2024, has an 89% completion rate. Another option is three months of rifapentine and isoniazid - taken once a week under direct observation. These shorter regimens aren’t just easier. They’re more effective at preventing TB reactivation. Don’t skip this step. Even if you feel fine. Latent TB has no symptoms. But once you start a TNF inhibitor, the bacteria can explode into active disease within weeks.Monitoring After You Start

Screening doesn’t end when you get your first injection. Most TB cases happen in the first six months. In fact, half of all cases show up within the first three months. You need to check in regularly. Every three months, your doctor should ask: Have you had a fever? Night sweats? Unexplained weight loss? A cough that won’t go away? These aren’t just cold symptoms - they’re red flags. And here’s something many doctors miss: TB on TNF inhibitors often isn’t in the lungs. Up to 78% of cases are extrapulmonary - meaning it’s in the spine, brain, liver, or bloodstream. That makes diagnosis harder. A chest X-ray might look normal, but you could still have TB in your spine or lymph nodes. If you develop symptoms, don’t wait. Get tested immediately. A sputum test, blood culture, or tissue biopsy may be needed. Delaying treatment increases the risk of death.What Happens If TB Comes Back

If you develop active TB while on a TNF inhibitor, you stop the drug immediately. You start a full course of anti-TB antibiotics - usually four drugs for two months, then two drugs for four more. But here’s the twist: when you start TB treatment, your immune system can overreact. This is called TB-IRIS - immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. It happens when your immune system, suppressed by the TNF inhibitor, suddenly wakes up and starts attacking the TB bacteria too hard. The result? Fever, swelling, pain - sometimes worse than the infection itself. TB-IRIS occurs in about 13% of cases. It often shows up 45 to 110 days after starting TB treatment. Steroids are usually needed to calm the inflammation. In one study, patients needed an average of 60 mg of prednisone daily for nearly a year.

siva lingam

January 23, 2026 AT 13:18So let me get this straight - we’re giving people life-changing meds but telling them to get tested for a disease that might not even show up on the test? And if it’s negative, we still treat them anyway? Sounds like a bureaucratic bingo card.

Also, why is everyone acting like this is new? I’ve seen this play out in Indian clinics for years. Negative test? Cool. Start drug. Three months later - ‘oh hey, my spine is on fire.’

Meanwhile, the clinic lost the paperwork. Again.

Phil Maxwell

January 24, 2026 AT 09:23Been on adalimumab for 4 years. Got the IGRA and TST before starting. Both negative. Still get checked every 3 months - fever, night sweats, cough? Nope. No weight loss. Just tired. Which is normal when you have RA anyway.

But I do always mention it. Just in case. Better safe than sorry, right?

Shelby Marcel

January 25, 2026 AT 09:09wait so if u r from india and u get a neg tst u still get treated? like even if u never had tb? that seems kinda wild. i thought the test was supposed to be reliable. or is it just… broken in high burden areas?

also why does everyone say ‘latent tb’ like its a secret club. tb is tb. why the code words?

Tommy Sandri

January 26, 2026 AT 03:42The clinical guidelines presented here are both evidence-based and pragmatic. The distinction between soluble receptor blockers and monoclonal antibodies is clinically significant and supported by multiple cohort studies.

Furthermore, the recommendation for empirical latent TB treatment in high-burden populations aligns with WHO and CDC consensus. The cost-benefit analysis favors prophylaxis over reactive management, particularly given the morbidity and mortality associated with disseminated TB.

Systemic implementation remains a challenge, but the framework is sound.

Sushrita Chakraborty

January 26, 2026 AT 03:55As someone from Kolkata, I’ve seen this firsthand. My uncle was on etanercept - negative IGRA, negative TST. He developed TB meningitis six months later. The doctors said, ‘It’s rare.’ But ‘rare’ doesn’t help when you’re burying someone.

Why isn’t everyone getting a chest CT before starting? Why are we relying on tests that miss 18%? We’re gambling with lives because of cost and convenience.

And yes - the four-month rifampin-isoniazid regimen is a miracle. Why isn’t it standard everywhere? Why do we still use nine months of isoniazid like it’s 1987?

Also, TB-IRIS is terrifying. I know a woman who needed prednisone for 14 months. Her joints flared. Her vision blurred. She lost 30 pounds. All because her immune system ‘woke up’ too hard.

This isn’t just medicine. It’s survival.

Josh McEvoy

January 27, 2026 AT 17:30tb on tnf inhibitors?? bro that’s like letting a bear loose in a library 🐻📚

also why do doctors act like they just discovered this?? i’ve been on adalimumab since 2019 and every single time i go in they ask ‘any night sweats??’ like i’m a detective in a noir film 😭

also tb in the spine?? my back already hurts from sitting at my desk. now i’m scared to sneeze 😵💫

Heather McCubbin

January 28, 2026 AT 02:10They say vigilance is the key but no one talks about how the system is rigged

It’s not about the drugs. It’s about who gets care. If you’re poor, you get a TST in a clinic that doesn’t even have a fridge for the reagents. If you’re rich, you get IGRA, a specialist, and a follow-up text reminder.

We treat TB like a glitch in the system instead of a predictable consequence of modern medicine

And we call it ‘prevention’ while people die because they can’t afford the test

Wake up. This isn’t science. It’s capitalism with a stethoscope

Sawyer Vitela

January 28, 2026 AT 09:44Etanercept has lower TB risk. End of story.

IGRA false negatives are well documented.

Extrapulmonary TB is common on biologics.

Four-month rifampin/isoniazid is superior.

Stop overcomplicating it.

Elizabeth Cannon

January 29, 2026 AT 07:44Hey - if you’re reading this and you’re on a TNF inhibitor, I want you to know: you’re not alone.

I’ve been on infliximab for 7 years. I’ve had three TB screens. Two were negative. One was indeterminate. I still get checked every 3 months. My nurse calls me. She remembers my name.

That’s what matters. Not just the test. The person behind it.

And if you’re scared? Say it. Even if you think it’s dumb. ‘I’ve had a weird cough for two weeks.’ That’s not weak. That’s smart.

You deserve to live. Not just survive.

Gina Beard

January 30, 2026 AT 23:29The real tragedy isn’t the TB. It’s that we treat inflammation like a puzzle to solve - not a conversation with the body.

We silence TNF to stop pain. But we forget it’s also the voice that keeps the past buried.

Maybe the real question isn’t how to prevent TB.

But why we keep asking the body to forget things it was never meant to forget.