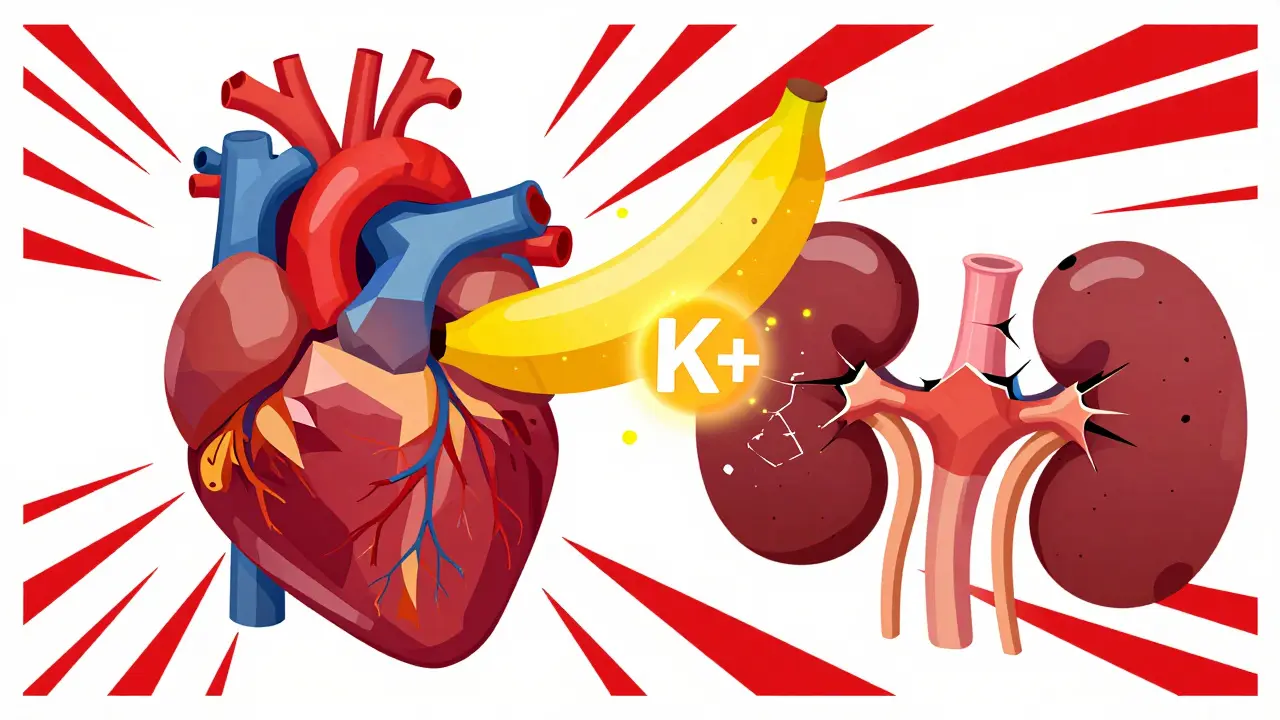

When your kidneys aren't working well, even foods you love can become dangerous. For people with chronic kidney disease (CKD), too much potassium in the blood - a condition called hyperkalemia - can trigger heart rhythm problems, muscle weakness, or even sudden cardiac arrest. This isn't just a theoretical risk. About 40-50% of people with advanced CKD experience elevated potassium levels, and it’s one of the most common reasons they end up in the emergency room. The good news? We now have better tools than ever to manage it - but only if you understand the rules.

What Is Hyperkalemia and Why Does It Happen in CKD?

Hyperkalemia means your serum potassium level is above 5.0 mmol/L. Normal is 3.5 to 5.0. But in CKD, your kidneys can’t flush out the extra potassium from your diet. That’s because kidney function declines over time. By stage 4 or 5 (eGFR below 30 mL/min), you’re losing the ability to regulate this mineral - even if you eat normally.

Here’s the twist: many of the best medications for protecting your heart and kidneys - like ACE inhibitors, ARBs, and MRAs - make hyperkalemia worse. These drugs block the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS), which normally helps the kidneys excrete potassium. So doctors face a real dilemma: keep the drugs on and risk high potassium, or lower them and lose their protective effects. Studies show that cutting back on these medications increases the risk of heart attack and kidney failure by up to 34%.

Dietary Limits: How Much Potassium Is Safe?

Not all CKD patients need the same diet. Your potassium limit depends on how far your kidney disease has progressed.

- Stages 1-3a (mild to moderate CKD): No need to restrict unless your potassium is already high. A “prudent” approach means avoiding excessive amounts of high-potassium foods - not eliminating them.

- Stages 3b-5 (advanced CKD, not on dialysis): Strict limit of 2,000 to 3,000 mg per day. That’s about 51 to 77 mmol. For reference, one medium banana has 422 mg. One baked potato? 421 mg. A cup of orange juice? 181 mg. You can hit your daily limit with just two bananas and a large baked potato.

Many patients struggle with this. A 2023 survey found only 37% of CKD patients consistently stick to their potassium limits. Why? Because potassium is everywhere - in fruits, vegetables, beans, dairy, nuts, and even salt substitutes. A dietitian can help you learn which foods are safe in what amounts. For example, leaching potatoes by soaking them in water for 2 hours before cooking can cut potassium by up to 50%. Choosing white bread over whole grain, rinsing canned beans, and avoiding tomato sauce can make a real difference.

Emergency Treatment: What Happens When Potassium Hits 6.0?

If your potassium rises above 5.5 mmol/L and you have ECG changes - like tall, peaked T-waves - you’re in a medical emergency. At 6.0 mmol/L or higher, your heart’s electrical system can shut down. This isn’t something you wait on. Immediate treatment is critical.

Here’s what doctors do in the ER:

- Calcium gluconate (10 mL of 10% solution IV): Given over 2-5 minutes. This doesn’t lower potassium - it just protects your heart muscle from the effects of high potassium. It works within 1-3 minutes and lasts about an hour. If your ECG shows a widened QRS complex (a sign of severe hyperkalemia), this is the first step.

- Insulin and glucose (10 units regular insulin + 50 mL of 50% dextrose): This pushes potassium into your cells. It lowers levels by 0.5 to 1.5 mmol/L within 30 minutes. But there’s a catch: about 10-15% of patients develop low blood sugar. That’s why glucose is given with it.

- Sodium bicarbonate (50-100 mmol IV): Only if you’re also acidotic (bicarbonate <22 mmol/L). It works fast - within 5-10 minutes - by shifting potassium into cells. But it’s not effective if your pH is normal.

These are temporary fixes. They don’t remove potassium from your body. That’s why the next step is always to get potassium out - through dialysis or binders.

Chronic Management: The New Generation of Potassium Binders

For long-term control, we’ve moved far beyond old-school treatments. Sodium polystyrene sulfonate (SPS) was once the go-to binder. But it’s messy: it causes constipation, colonic necrosis (a rare but deadly gut injury), and adds a lot of sodium - bad news for people with heart failure or high blood pressure.

Today, two newer drugs dominate:

- Patiromer (Veltassa): Taken once daily. It binds potassium in the gut and removes it through stool. It’s sodium-free, which makes it safer for heart patients. But it can cause low magnesium (18.7% of users) and constipation (14.2%). Many patients stop taking it because of its chalky texture - 22% quit due to taste alone.

- Sodium zirconium cyclosilicate (SZC, Lokelma): Taken twice daily. It works faster - reducing potassium by 1.0-1.4 mmol/L within just one hour. That’s why it’s the drug of choice for acute episodes. But it adds sodium: about 1.2 grams per day. That can worsen swelling in heart failure patients (12.3% vs. 4.7% with patiromer).

Here’s the key: these drugs aren’t just for emergencies. They let people stay on life-saving RAAS inhibitors. In clinical trials, 78% of patients on patiromer maintained their full RAAS dose, compared to only 38% without a binder. With SZC, 83% kept their MRA therapy. That’s huge. Staying on these drugs cuts your risk of death and kidney failure.

Monitoring, Adherence, and Real-World Challenges

Managing hyperkalemia isn’t just about pills and diet. It’s about consistent monitoring and support.

- Check your potassium level 1-2 weeks after starting or increasing a RAAS inhibitor.

- Once stable, test every 3-6 months.

- If you feel muscle weakness, palpitations, or dizziness - get tested immediately.

But adherence is a major problem. A 2023 study of nephrology clinics found that when patients got automatic reminders and dietitian follow-ups every 3 months, RAASi continuation jumped from 52% to 81%. Electronic alerts in medical records help too - triggering pharmacist reviews when potassium hits 5.0 mmol/L or higher.

Cost is another barrier. In the U.S., SPS costs about $47 a month. Patiromer? Around $635. SZC? About $600. Many community clinics still use SPS because it’s cheap - even though it’s less safe. Only 47.6% of community practices use newer binders, compared to 82.4% in academic centers.

And then there’s quality of life. A 2023 survey by the American Kidney Fund found that 45% of CKD patients feel socially isolated because they can’t eat with family or go out to restaurants. Imagine not being able to have a banana at breakfast, or potatoes with dinner, or a glass of orange juice. It’s not just medical - it’s emotional.

What’s Next? Precision and Digital Tools

The future of hyperkalemia management is getting smarter. Researchers are testing apps that scan food barcodes and instantly calculate potassium content. Pilot studies show these tools improve dietary adherence by 32%. Other innovations include:

- Urinary potassium tests to personalize diet limits instead of using fixed numbers.

- New drugs like tenapanor, which blocks potassium absorption in the gut without systemic effects.

- Encapsulated binding polymers in early trials that reduce potassium by 1.2 mmol/L in 24 hours.

By 2027, experts predict that 75% of CKD patients on RAAS inhibitors will be on a potassium binder. That’s a huge shift - from accepting high potassium as inevitable, to treating it as a manageable condition.

The bottom line? You don’t have to choose between heart protection and safety anymore. With the right diet, the right meds, and the right monitoring, you can live well - even with advanced CKD.

Brooke Exley

February 23, 2026 AT 05:37Alfred Noble

February 24, 2026 AT 22:44Matthew Brooker

February 25, 2026 AT 13:58Emily Wolff

February 26, 2026 AT 10:31William James

February 27, 2026 AT 11:46Vanessa Drummond

February 28, 2026 AT 04:02Spenser Bickett

February 28, 2026 AT 08:11Christopher Wiedenhaupt

February 28, 2026 AT 11:42John Smith

March 1, 2026 AT 03:16Shalini Gautam

March 2, 2026 AT 16:21Brooke Exley

March 3, 2026 AT 06:25