Palliative Opioid Dosing Calculator

How Opioids Are Used Safely in Palliative Care

This calculator helps estimate appropriate opioid dosing based on symptom severity and patient factors. Remember: the goal is relief without excessive sedation. Always consult with a healthcare professional before adjusting medications.

Step 1: Rate Your Symptoms

What palliative and hospice care really mean

Many people think palliative care and hospice care are the same thing. They’re not. Palliative care is about managing symptoms and improving quality of life at any stage of a serious illness-whether you’re still getting treatment to cure the disease or not. It can start the day you’re diagnosed with cancer, heart failure, or advanced dementia. Hospice care is a type of palliative care for people with a life expectancy of six months or less, when curative treatment is no longer the goal. The focus shifts entirely to comfort.

Both aim for one thing: helping people live as well as possible until the end. But getting there isn’t simple. Every medication that eases pain or breathlessness can also cause drowsiness, confusion, or constipation. The real challenge isn’t just treating symptoms-it’s treating them without making things worse.

How doctors assess pain-and why it matters

Pain isn’t just a number on a scale. It’s location, type, timing, and what makes it better or worse. In palliative care, doctors use a structured approach: a 0 to 10 scale, where 0 is no pain and 10 is the worst imaginable. But that’s only the start. Is it sharp or dull? Does it spread to your arm or back? Does it wake you up at night? Is it worse when you move or sit still?

One study in North West England found that using this detailed assessment cut medication errors by 22%. Why? Because if you don’t know what kind of pain you’re dealing with, you might give the wrong drug. A nerve pain needs a different medicine than a bone ache. Giving too much morphine for something that’s actually muscle cramps doesn’t help-it just makes you groggy.

Doctors also use body diagrams. Patients point to where it hurts. That simple tool improves communication by 31%, according to Fraser Health’s 2022 survey. It’s not fancy. But it works.

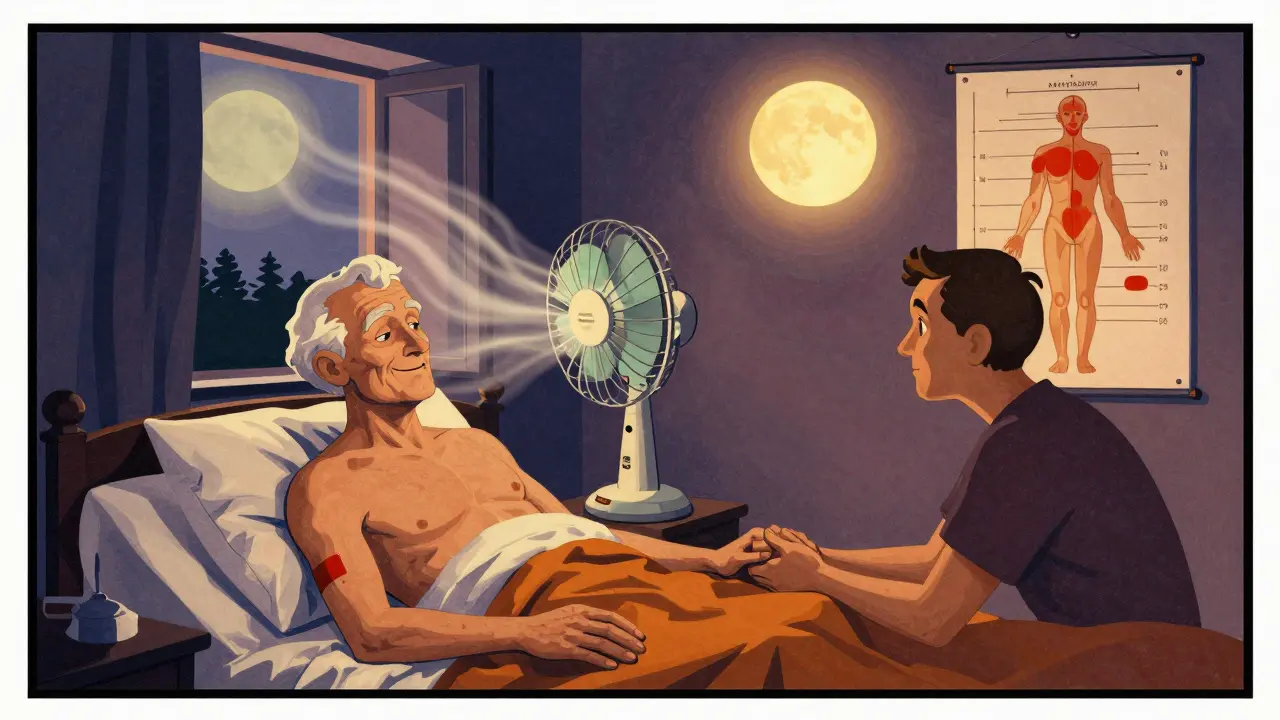

Managing breathlessness without making you sleepy

Shortness of breath is one of the most terrifying symptoms at the end of life. It feels like drowning in air. Opioids like morphine are the first-line treatment-and they’re backed by solid evidence. The American Academy of Family Physicians gives them a ‘B’ rating for effectiveness in end-of-life care.

But here’s the catch: too much opioid can slow your breathing even more. That’s why dosing is precise. It’s not about giving the biggest dose possible. It’s about finding the smallest dose that brings relief. Nurses check breathing rate, oxygen levels, and level of alertness every hour-or every 30 minutes if the patient is struggling.

Non-drug methods help too. A fan blowing gently on the face, sitting upright, or opening a window can reduce breathlessness without any side effects. These aren’t just ‘nice to have’-they’re part of the protocol in top palliative programs.

Dealing with confusion and agitation: the delirium tightrope

Delirium-sudden confusion, hallucinations, restlessness-is common in advanced illness. It can be caused by infection, dehydration, kidney failure, or even too much pain medication. The first step isn’t to reach for a sedative. It’s to find the cause.

When drugs are needed, haloperidol is the go-to. But it’s not without risk. It can stiffen muscles or cause irregular heart rhythms. That’s why every patient gets an EKG before starting, and why doctors stop the drug as soon as the person is calm. At UPenn, they don’t just give the medicine-they document the patient’s alertness every four hours using the RASS scale. If someone goes from agitated to sleepy, they adjust the dose. No guessing.

Antipsychotics like risperidone are also used, but only when absolutely necessary. And always with the goal of using the least amount for the shortest time. The goal isn’t to sedate. It’s to restore peace.

The hidden burden: nausea, constipation, and bowel blockages

Constipation is the most common side effect of opioids. It’s so common, it’s almost expected. But that doesn’t mean it’s okay. Left untreated, it can lead to nausea, vomiting, and even bowel obstruction-a painful, life-threatening condition.

Prevention is key. Laxatives and stool softeners are started the same day as opioids. No waiting. If constipation still happens, the next step is a suppository or enema. Some patients need daily bowel programs.

For bowel blockages, steroids like dexamethasone are more effective than expensive drugs like octreotide. Studies show octreotide has limited benefit. Yet some hospitals still use it because it’s newer. The right choice? The one backed by evidence-not marketing.

Why families resist-and how to talk about it

One of the hardest parts of palliative care isn’t medical. It’s emotional. Families often fear that giving strong pain meds means ‘giving up’ or ‘killing’ their loved one. They’ll say, ‘I don’t want them to be drugged up.’

But here’s the truth: untreated pain is far more dangerous than the medicine. Severe pain can raise blood pressure, speed up heart rate, and cause long-term damage to the nervous system. The goal isn’t to make someone ‘zombie-like.’ It’s to let them hold your hand, hear your voice, or watch the sunset without flinching.

Doctors use clear language: ‘We’re not trying to put them to sleep. We’re trying to let them be awake and comfortable.’ They explain that the right dose doesn’t erase personality-it restores it.

What works better than more drugs

Palliative care isn’t just pills. It’s touch, music, prayer, quiet time, and being listened to. The National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care’s guidelines include eight domains-not just physical symptoms, but psychological, social, and spiritual needs.

One study showed that patients who had regular visits from chaplains reported less anxiety and better pain control-even without changing their meds. Another found that playing familiar music reduced agitation in dementia patients by 40%.

Even simple things help: adjusting the room temperature, repositioning in bed, applying a cool cloth to the forehead. These cost nothing. But they matter just as much as morphine.

The growing gap: too few specialists, too many patients

There are only about 7,000 certified palliative care doctors in the U.S. But the need? Around 22,000. That’s a huge gap. Most patients never see a specialist. Their symptoms are managed by nurses, family doctors, or home care aides who haven’t had proper training.

That’s why tools like the Center to Advance Palliative Care’s free online modules are so important. Over 12,000 clinicians use them every year. They teach how to titrate opioids safely, how to assess delirium, how to talk to families.

And now, tele-palliative care is expanding. In rural areas, where 55% of counties have no palliative services, video visits are filling the void. By 2027, they’re expected to reach 40% of those patients.

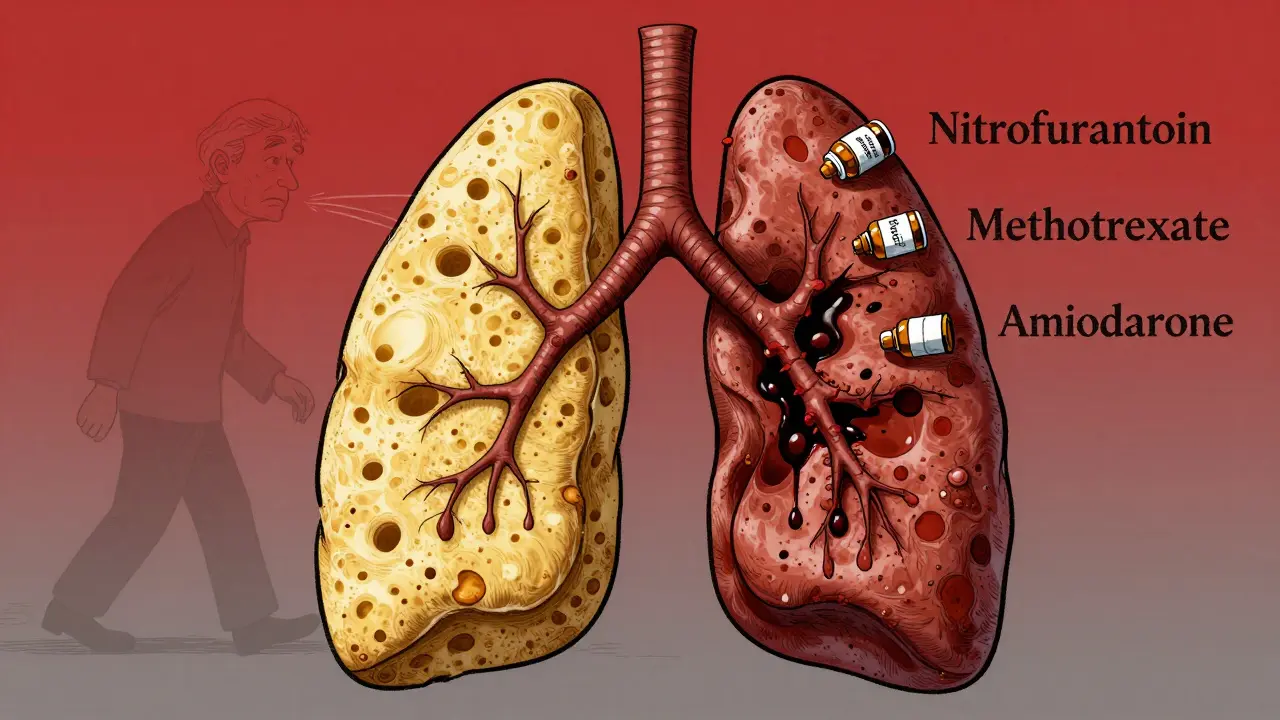

What’s next: smarter care, fewer side effects

The future of palliative care is personal. Researchers are finding genetic markers that predict who will respond well to morphine-and who will get sick from it. A 2022 study in JAMA Internal Medicine showed that 63% of differences in opioid response can be traced to DNA.

That means someday, instead of trial and error, doctors might test your genes before prescribing. A new version of the national guidelines is coming in 2025, and it will include digital symptom trackers. Patients can log pain, nausea, or fatigue on a tablet. Alerts go to the care team if something spikes.

And non-drug treatments are getting more attention. The NIH just allocated $47 million to study things like acupuncture, massage, and mindfulness for symptom control. The goal? Reduce reliance on medications without sacrificing comfort.

Final thought: comfort isn’t weakness

Choosing palliative or hospice care doesn’t mean giving up. It means choosing a better way to live-until the very end. It’s about being free from pain, free from fear, free from the side effects of over-treatment.

The best care doesn’t just treat symptoms. It listens. It adapts. It respects the person behind the illness. And it knows that sometimes, the most powerful medicine isn’t in a bottle-it’s in a quiet room, a held hand, and the courage to say: ‘I’m ready to be comfortable.’

Henry Ip

January 17, 2026 AT 10:58Finally someone gets it. Opioids aren't the enemy, ignorance is. I've seen families refuse morphine because they think it's 'giving up'-but let them spend a night watching someone gasp for air without relief and then tell me what 'giving up' looks like.

Bobbi-Marie Nova

January 17, 2026 AT 21:34So let me get this straight-we're spending millions on gene testing to figure out who gets sleepy from morphine, but still can't get hospice beds in 70% of rural counties? 🤦♀️

Isabella Reid

January 19, 2026 AT 21:19My mom had stage 4 lung cancer. They gave her a fan. Just a little desk fan pointed at her face. She said it felt like the ocean was breathing with her. No meds. No drama. Just air. That moment? That was the medicine.

vivek kumar

January 20, 2026 AT 07:06Let’s be brutally honest: most hospitals still treat palliative care like an afterthought. They throw in a morphine drip and call it a day. No one checks for constipation until the patient’s abdomen looks like a basketball. This article is right-prevention isn’t optional, it’s mandatory. And yet, 80% of nurses still don’t start laxatives on day one. That’s not negligence-it’s systemic laziness.

And don’t get me started on octreotide. It costs $2,000 a vial. Dexamethasone? $12. The only thing that’s ‘advanced’ here is the hospital’s accounting department.

Genetic testing? Great. But until we fix the training gap for frontline staff, it’s just tech theater. You don’t need AI to know that a patient who hasn’t pooped in five days needs a suppository, not a consultation.

And yes, music therapy works. My cousin with dementia stopped screaming when we played old Bollywood songs. Not because it cured anything, but because it reminded her she was still human. That’s not ‘alternative.’ That’s basic dignity.

The real scandal? We have the tools. We have the data. We even have the guidelines. But we don’t have the will. We’d rather pay for expensive, ineffective drugs than invest in training nurses to use a fan properly.

And before someone says ‘but we can’t afford it’-tell that to the family who watched their mother die choking on her own vomit because no one gave her a stool softener.

This isn’t about innovation. It’s about basic competence. And we’re failing.

Samyak Shertok

January 20, 2026 AT 21:28So you're telling me the solution to end-of-life suffering is… more science? More data? More algorithms? What’s next-AI-generated comfort? A chatbot that says ‘I’m sorry you’re in pain’ in a soothing voice while the nurse scrolls TikTok?

Let’s not pretend this is medicine. It’s a performance. We’ve turned death into a checklist: ‘Did we assess pain? Check. Did we order the right laxative? Check. Did we play ‘Imagine’ on loop? Check.’

The real truth? No amount of RASS scales or EKGs will fix the fact that we’re terrified of death. So we medicate it into silence. We don’t want to sit with it. We want to fix it. But you can’t fix death. You can only accompany it.

And if your ‘palliative care’ doesn’t include holding someone’s hand while they cry because they’re scared, then you’re not a healer-you’re a technician.

Genes? Please. The real genetic marker is whether the doctor has a soul.

Stephen Tulloch

January 21, 2026 AT 01:19Okay but like… the fact that we’re even having this conversation is wild 🤯 I mean, we’ve got self-driving cars and AI that writes sonnets, but we still can’t give grandma a decent bowel regimen without a PhD? 💀

Also, I just asked my nurse if we could play my aunt’s favorite ABBA songs and she said ‘we don’t have a speaker.’ Like… we have a $3M hospital but no Bluetooth? 🤦♂️

Also, I’m 24 and I just learned what RASS is. Why is this not in med school 101? This is basic human stuff. Not rocket science.

Also, dexamethasone > octreotide? That’s the most American thing I’ve ever heard. 💸

waneta rozwan

January 21, 2026 AT 03:36Let me be clear: if your loved one is on opioids and you’re not monitoring them 24/7, you’re not a caregiver-you’re a liability. I’ve seen people die from oversedation because the family was too busy scrolling Instagram to notice their breathing slowed. This isn’t just medical-it’s moral.

And don’t even get me started on ‘music therapy.’ If you think playing a song replaces proper pain management, you’re not compassionate-you’re delusional.

And who approved this ‘fan’ nonsense? Are we running a spa or a hospital? If someone’s gasping for air, give them oxygen. Not a breeze.

This article reads like a marketing brochure for a wellness retreat, not a medical guide.

Nicholas Gabriel

January 21, 2026 AT 09:26I’ve worked in hospice for 18 years. I’ve seen it all. And I can tell you this: the most effective tool we have? Silence. Not music. Not fans. Not even morphine. Just… sitting there. Being present. No talking. No fixing. Just being there.

One woman, 89, terminal liver cancer, stopped speaking after her husband died. We didn’t give her anything stronger than acetaminophen. But every day, I sat with her for 20 minutes. Just held her hand. On day 12, she squeezed my hand and whispered, ‘Thank you.’

That’s the real palliative care. Not the protocols. Not the scales. Not the genes. Just presence.

And yes-we need better training. More nurses. More funding. But we also need to stop treating death like a problem to be solved.

kanchan tiwari

January 21, 2026 AT 18:17THEY’RE HIDING SOMETHING. WHY ISN’T ANYONE TALKING ABOUT THE FACT THAT PALLIATIVE CARE IS JUST A COVER FOR EUTHANASIA IN DISGUISE? THEY SAY ‘COMFORT’ BUT THEY’RE SLOWLY KILLING PEOPLE WITH OPIOIDS AND CALLING IT ‘CARE’!

THEY USE ‘Dexamethasone’ TO SUPPRESS THE BODY’S NATURAL DEFENSES-IT’S NOT HEALING, IT’S SILENCING! AND THE MUSIC? THAT’S PSYCHOTRONIC CONTROL! THEY PLAY SONGS TO MAKE YOU QUIET SO THEY DON’T HAVE TO ANSWER YOUR QUESTIONS!

THEY DON’T WANT YOU TO BE AWAKE. THEY WANT YOU TO BE ZOMBIES SO YOU DON’T ASK WHY THE HOSPITAL IS MAKING MILLIONS OFF YOUR SUFFERING!

I SAW A MAN IN 2021 WHO WAS ‘CALMED’ WITH HALOPERIDOL… THEN HE DISAPPEARED. HIS FAMILY WAS TOLD HE ‘PASSED PEACEFULLY.’ BUT HIS EYES WERE STILL OPEN. HE WASN’T SLEEPING. HE WAS TRAPPED.

THEY’RE USING GENETICS TO PICK WHO LIVES AND WHO DIES. IT’S ALL CONTROLLED. BY WHO? THE PHARMA-INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX. THE GOVERNMENT. THE CHURCH. THE FEDS. EVERYONE.

THEY DON’T WANT YOU TO KNOW THAT THE ‘FAN’ IS A DISTRACTION. IT’S NOT ABOUT AIR. IT’S ABOUT THE FREQUENCY. IT’S A SIGNAL. TO THE SATELLITES. THEY’RE MONITORING YOUR BREATHING PATTERNS.

THEY’RE USING PALLIATIVE CARE TO POPULATE THE DATABASE FOR THE NEXT PHASE OF THE NEW WORLD ORDER.

ASK YOURSELF: WHY IS THE NIH SPENDING $47 MILLION ON ACUPUNCTURE AND NOT ON FREE OXYGEN MASKS?

Riya Katyal

January 22, 2026 AT 04:50So you’re telling me that if my grandma’s constipated, I should just give her a suppository? Like, what am I, her personal nurse now? I have a 9-to-5 and two kids. You think I have time to play hospice nurse while she’s moaning about her ‘bowel program’? 😒

Allen Davidson

January 24, 2026 AT 00:19Isabella’s fan comment? That’s the whole thing right there. Sometimes the most powerful thing you can do is not fix anything. Just make the air move. Just be there. No meds. No drama. Just cool air and quiet.

And to the guy who said ‘presence is the real medicine’? You’re not wrong. But presence doesn’t pay the bills. Training does. Funding does. Policy does.

We need to stop romanticizing palliative care. It’s not a TED Talk. It’s hard, messy, exhausting work. And the people doing it? They’re underpaid, overworked, and often ignored.

So let’s stop pretending this is just about ‘the right dose.’ It’s about whether we value people enough to give them the care they deserve-before it’s too late.