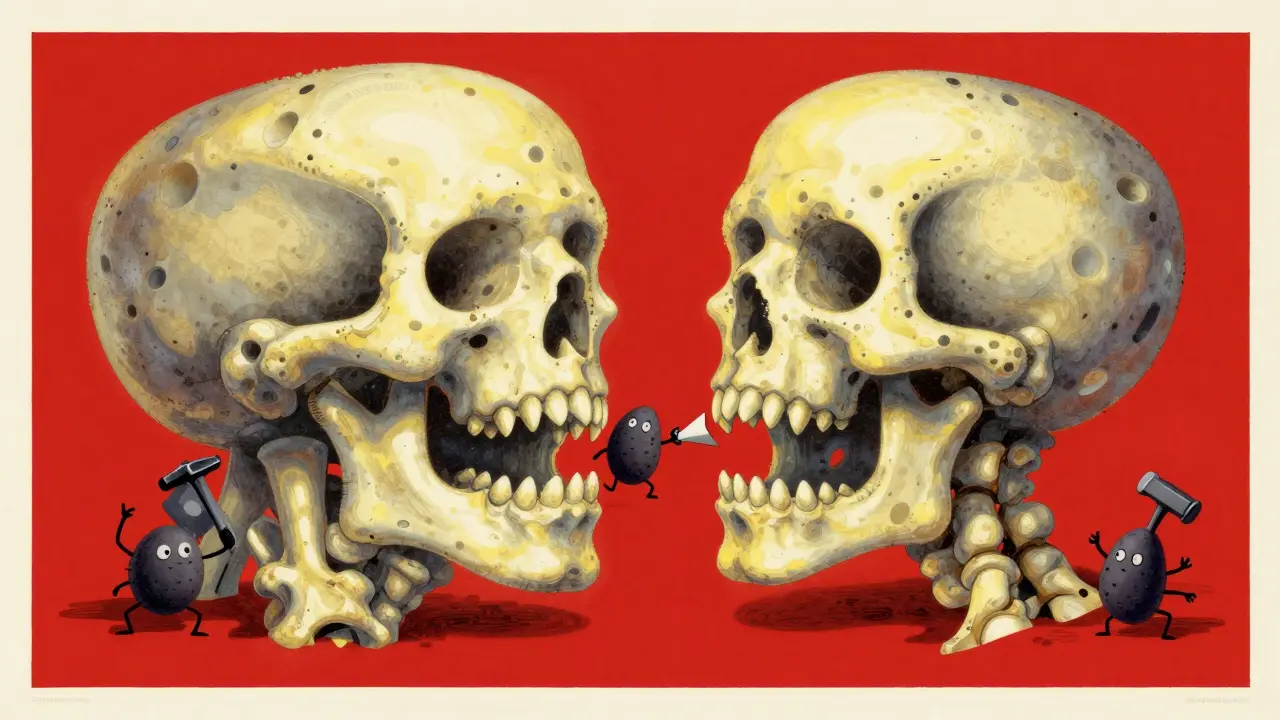

What Parkinson’s Disease Really Does to Your Body

Imagine your muscles suddenly refusing to listen. Your hand shakes when you’re trying to hold a coffee cup. Getting out of a chair feels like climbing a hill. Buttons on your shirt turn into puzzles. This isn’t just aging - it’s Parkinson’s disease. At its core, Parkinson’s is a brain disorder where nerve cells that make dopamine slowly die off. By the time symptoms show up, you’ve already lost 60 to 80% of those cells. That’s why movement becomes hard, slow, or stiff. It’s not just about shaking. It’s about your brain losing the signal that tells your body how to move smoothly.

The Three Signs You Can’t Ignore

Most people with Parkinson’s notice three things first: tremor, stiffness, and slowness. The tremor isn’t like the kind you get from caffeine. It’s a quiet, rhythmic shaking - often starting in one hand, usually when you’re resting. Doctors call it a "pill-rolling tremor" because it looks like you’re rolling a pill between your thumb and finger. It fades when you reach for something, and it disappears when you sleep. But stress, fatigue, or strong emotions can make it worse.

Stiffness, or rigidity, hits harder than you’d think. It’s not just tight muscles. It’s like your joints are locked in place. Some people describe it as "lead-pipe" stiffness - constant resistance. Others feel a ratcheting "cogwheel" feeling when someone moves their arm. This stiffness makes everyday tasks brutal. Writing becomes messy. Tying shoelaces takes forever. Even smiling can feel forced. Around 73% of people with Parkinson’s struggle with these small movements within the first three years.

Slowness - called bradykinesia - is the quietest symptom, but the most disabling. It’s not laziness. It’s your brain taking longer to send the signal to move. Walking gets smaller steps. Your arm doesn’t swing when you walk. You might freeze mid-step, especially when turning or walking through doorways. This isn’t something you can push through. It’s your nervous system failing to keep up.

Why Dopamine Is the Key

Dopamine isn’t just a "feel-good" chemical. It’s the conductor of your movement orchestra. It lives in a part of the brain called the substantia nigra. When those cells die, the signals to your muscles get scrambled. The result? Tremor, stiffness, slowness. The goal of treatment isn’t to stop the disease. It’s to replace what’s missing - dopamine.

But here’s the catch: you can’t just take a dopamine pill. Your body won’t let it cross into your brain. So doctors use levodopa - a chemical your body can turn into dopamine. Levodopa is usually paired with carbidopa. Carbidopa stops levodopa from breaking down in your stomach and blood, so more of it reaches your brain. This combo - carbidopa/levodopa - has been the gold standard since the 1970s. About 75% of people see big improvements in movement within an hour of taking it.

How Medication Works - and When It Stops Working

When you first start levodopa, it feels like a miracle. You move again. You write clearly. You walk without freezing. This is the "honeymoon period" - usually lasting 5 to 10 years. But then things change. The same dose doesn’t last as long. You start having "wearing-off" episodes - your good hours shrink from 6 to 3. Then come the unpredictable "on-off" swings: one minute you’re fine, the next you’re stuck.

And then there’s dyskinesia - involuntary, dance-like movements. It’s not the disease. It’s the side effect of too much dopamine in the brain. About 40 to 50% of people on long-term levodopa get this. It’s ironic: the medicine that gives you movement starts stealing it back. One patient on a Parkinson’s forum said, "After 8 years, my good hours are gone. I’m shaking not from the disease - but from the pill."

That’s why doctors now start lower and go slower. Instead of jumping to 100 mg, they might begin with 25/100 mg once a day. They wait. They watch. They adjust. The goal isn’t to eliminate every tremor - it’s to keep you moving without turning you into a puppet with jerky limbs.

Alternatives to Levodopa

Not everyone starts with levodopa. For younger patients - under 60 - doctors sometimes begin with dopamine agonists like pramipexole or ropinirole. These drugs mimic dopamine directly. They’re about half as strong as levodopa, but they’re less likely to cause dyskinesia early on. One person shared: "Starting pramipexole at diagnosis kept me stable for five years with no major side effects."

But these drugs come with their own problems: dizziness, nausea, sleepiness, even impulse control issues like gambling or overeating. About 60% of people end up needing both levodopa and a dopamine agonist as the disease moves forward. It’s not failure. It’s strategy.

Timing, Food, and the Hidden Enemy: Protein

Levodopa doesn’t play nice with protein. High-protein meals - steak, eggs, cheese, beans - compete with levodopa for the same pathway into your brain. If you take your pill with a burger, it might not work at all. That’s why many people learn to take their medication 30 to 60 minutes before meals. Some even switch to low-protein diets during the day.

Timing matters more than you think. Taking a pill at 8 a.m., 12 p.m., 4 p.m., and 8 p.m. sounds simple. But if you miss a dose by 20 minutes, your body knows. You feel it. One survey found that 56% of people say medication timing is their biggest daily challenge. And 72% say "wearing-off" makes it hard to cook, drive, or even talk on the phone.

There are newer options. Rytary is an extended-release version that lets you cut doses from four to two a day. But it costs $5,800 a year - nearly 10 times more than the generic. Inbrija is an inhaler for sudden "off" episodes. You inhale it, and in 10 minutes, you’re moving again. But it’s $3,700 a month. For most people, it’s not a daily fix - it’s an emergency tool.

The Real Cost - Beyond Money

Parkinson’s doesn’t just cost money. It costs time. In the early stages, managing meds takes 15 minutes a day. By the moderate stage, it’s 45 minutes. And 78% of people need help from a caregiver to keep track of pills, timing, meals, and side effects. It’s exhausting. It’s isolating. It turns your life into a medication schedule.

And it’s getting worse. The number of people with Parkinson’s is expected to double by 2040. The average annual cost in the U.S. is $22,800 - $11,900 of that is from lost work, missed days, and caregiving. This isn’t just a medical issue. It’s a social one.

What’s Next? Hope on the Horizon

Scientists aren’t giving up. There’s a new infusion therapy called Foslevodopa/foscarbidopa - a pump that delivers dopamine-like chemicals under the skin, 24/7. In a 2022 trial, patients gained 2.5 extra "on" hours a day. Gene therapies are being tested to help the brain make its own dopamine again. And a big study called the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative is looking for genetic clues to predict who responds best to which drug.

But for now, the best tool we have is still levodopa. Not because it’s perfect. But because it’s the most effective. The trick isn’t finding a cure - it’s learning how to use it wisely. Start low. Go slow. Watch for side effects. Time it right. And don’t be afraid to ask for help - from your doctor, your family, your community.

It’s Not Just About Movement

Parkinson’s doesn’t stop at tremors and stiffness. It affects sleep, mood, digestion, and even your sense of smell. But the fight for movement is the most visible. And the most personal. Because when you lose your ability to move, you lose a piece of your independence. Dopamine replacement doesn’t fix the brain. But it gives you back hours - maybe days - of your life. And sometimes, that’s enough.

Is Parkinson’s disease curable?

No, Parkinson’s disease is not curable yet. Current treatments focus on managing symptoms, especially movement problems, by replacing lost dopamine in the brain. While medications like levodopa can dramatically improve quality of life, they don’t stop the underlying nerve cell loss. Research is ongoing into gene therapies and neuroprotective drugs, but none have been proven to reverse or halt the disease.

Why does levodopa stop working over time?

Levodopa doesn’t stop working because the drug fails - it’s because the brain changes. As Parkinson’s progresses, fewer dopamine-producing cells remain to convert levodopa into dopamine. This makes the effect shorter and less predictable. Also, the brain’s receptors become oversensitive, leading to "wearing-off" periods and involuntary movements called dyskinesias. This is why doctors adjust doses, timing, and often add other medications as the disease advances.

Can you take levodopa with food?

It’s best to take levodopa 30 to 60 minutes before eating, especially meals high in protein. Protein uses the same transport system in the gut and blood-brain barrier as levodopa. If you eat a steak or cheese right before your pill, your body may block the medication from entering your brain. Many people find success by eating protein-heavy meals only at dinner, keeping breakfast and lunch light and carb-based.

Are dopamine agonists safer than levodopa?

They’re not safer - just different. Dopamine agonists like pramipexole and ropinirole are less likely to cause dyskinesia early on, which is why they’re often used in younger patients. But they come with their own risks: dizziness, swelling, sudden sleep attacks, and impulse control problems like gambling or binge eating. Levodopa is more effective for movement symptoms, but agonists are used to delay levodopa or boost its effect. Neither is "better" - it’s about matching the drug to the person.

How do I know if my medication timing is off?

Watch for patterns. If you notice your symptoms returning before your next dose - like stiffness or tremor coming back after 2 hours instead of 4 - that’s "wearing-off." If you suddenly feel stuck or frozen, then suddenly move well again without changing anything, that’s an "on-off" fluctuation. Keeping a daily log of when you take pills, when symptoms improve, and when they return helps your doctor adjust your schedule. Most people need to tweak timing every few months as the disease changes.

Is there a test to confirm Parkinson’s disease?

There’s no single blood test or scan that can definitively diagnose Parkinson’s. Doctors rely on a detailed medical history and a neurological exam - looking for tremor, stiffness, slowness, and balance issues. A dopamine transporter scan (DaTscan) can show reduced dopamine activity in the brain, but it can’t rule out other conditions. The diagnosis is clinical: if symptoms improve significantly with levodopa, that’s often the strongest confirmation.

Can lifestyle changes help with Parkinson’s symptoms?

Yes, but they don’t replace medication. Regular exercise - especially walking, dancing, tai chi, or boxing - has been shown to improve balance, mobility, and even mood. Physical therapy helps with stiffness and freezing. Speech therapy can address soft voice and swallowing issues. A balanced diet supports overall health, and avoiding high-protein meals around medication times improves drug effectiveness. Lifestyle doesn’t cure Parkinson’s, but it helps you live better with it.

Jillian Angus

December 23, 2025 AT 21:08Levodopa didn’t fix it. Just bought us time.

niharika hardikar

December 25, 2025 AT 04:59Steven Mayer

December 25, 2025 AT 13:55CHETAN MANDLECHA

December 26, 2025 AT 21:26Charles Barry

December 28, 2025 AT 01:18Rosemary O'Shea

December 28, 2025 AT 21:23Bhargav Patel

December 30, 2025 AT 14:43Ajay Sangani

December 30, 2025 AT 17:10Payson Mattes

December 31, 2025 AT 13:56Diana Alime

January 2, 2026 AT 00:18siddharth tiwari

January 3, 2026 AT 03:28