When a doctor gives a patient a biosimilar drug like Inflectra or Renflexis instead of the original biologic Remicade, the billing process isn’t as simple as switching one pill for another. Unlike generic pills, which are chemically identical and use the same billing code, biosimilars are complex biological products that require their own unique codes, payment rules, and documentation. This isn’t just paperwork-it directly affects how much providers get paid, how quickly biosimilars get adopted, and ultimately, how much patients pay out of pocket.

How Biosimilar Reimbursement Works Under Medicare Part B

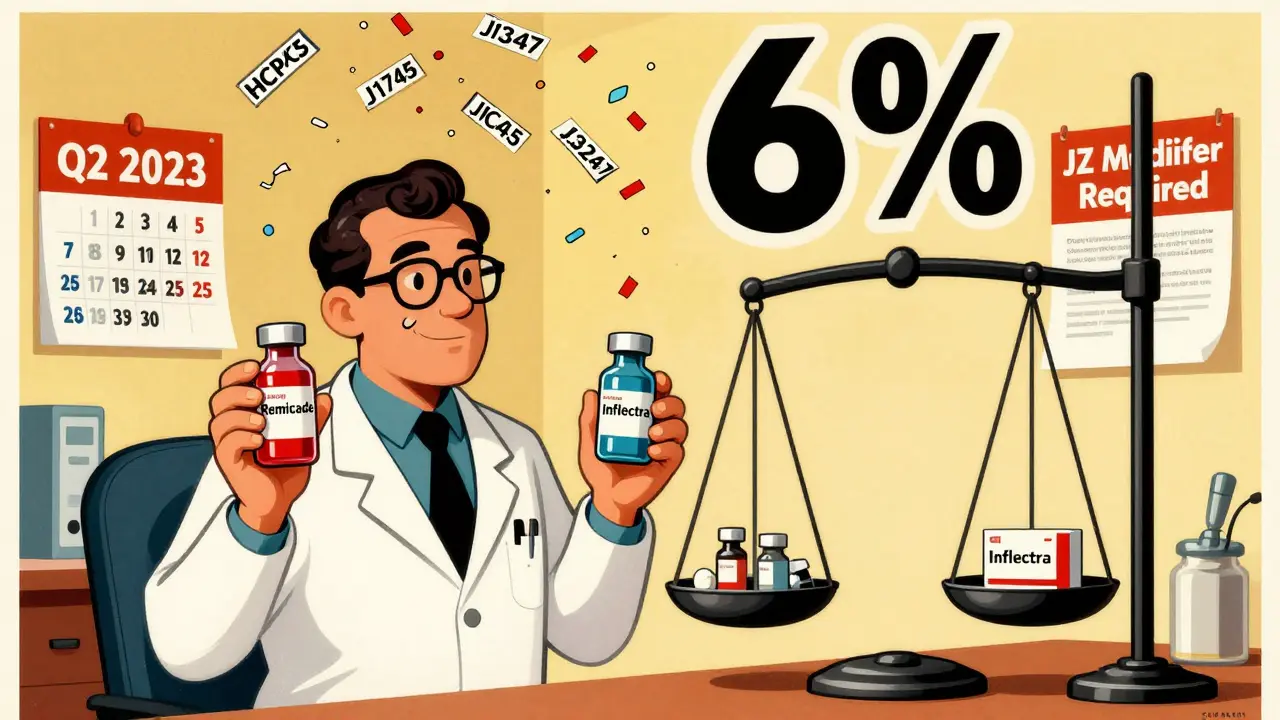

Medicare Part B covers drugs given in a doctor’s office or clinic, including most biologics and their biosimilars. The payment system is built around something called the Average Selling Price (ASP). For every biologic or biosimilar administered, Medicare pays 100% of that drug’s ASP, plus a 6% add-on fee. That’s the same formula used for the original reference product. But here’s the twist: the 6% add-on is calculated based on the reference product’s ASP, not the biosimilar’s.

For example, if Remicade (the reference product) sells for $2,500 per dose, the provider gets $150 in add-on revenue ($2,500 × 6%). If Inflectra (a biosimilar) sells for $2,000, the provider still gets $150 in add-on revenue-not $120 ($2,000 × 6%). That means the provider makes $30 more per dose by using the more expensive reference drug. This creates a financial incentive to stick with the brand-name product, even if the biosimilar is cheaper for the system as a whole.

The Shift from Blended Codes to Product-Specific Codes

Before 2018, all biosimilars for the same reference drug shared one HCPCS code-like Q5101 for infliximab biosimilars. Medicare paid a blended rate based on the average price of all biosimilars on the market. That created a problem: if one company launched a biosimilar at a low price, everyone else got paid more than they should’ve because the payment was pulled up by the average. It was a classic free-rider issue. Manufacturers had little reason to cut prices, since they’d still get paid the same as their competitors.

In January 2018, CMS flipped the script. Now, every FDA-approved biosimilar gets its own unique HCPCS code. Inflectra has J3247. Renflexis has J3248. Hadlima has J3249. Each one gets paid based on its own ASP plus 6% of the reference product’s ASP. This change made sense for transparency-now you can track exactly how much of each biosimilar is being used. But it didn’t fix the core problem: the add-on payment still favors the more expensive drug.

The JZ Modifier: A New Layer of Complexity

On July 1, 2023, CMS added another layer: the JZ modifier. This is required on all infliximab and infliximab biosimilar claims when no drug is discarded after preparation. That means if a provider uses every last drop of the vial-no waste-they must add JZ to the claim. If they discard even a drop, they don’t use it. This was meant to prevent overbilling for unused drug, but it’s created a paperwork headache. One gastroenterology practice in Ohio reported a 30% spike in billing staff time just to track vial usage and ensure correct modifier use.

And it’s not just infliximab. CMS is watching other high-volume biologics. The JZ modifier could expand to other drugs in 2025. Providers are scrambling to update their electronic health records and train staff. One oncology center in Texas said they lost $18,000 in denied claims in the first three months after JZ went live because their billing team didn’t know the rule.

Why Biosimilars Still Struggle to Gain Traction in the U.S.

Even though there are 32 FDA-approved biosimilars as of late 2023, their market share in the U.S. hovers around 35% for mature products like infliximab. In Europe, where pricing is more aggressive and reimbursement is based on the lowest-cost option, biosimilar adoption hits 75-85% within five years. Why the gap?

It’s not just the 6% add-on. It’s also how Medicare Advantage plans and private insurers handle payment. While Medicare Part B pays 106% of ASP, Medicare Advantage plans often pay 100-103%, and commercial insurers vary wildly. Some pay full ASP. Some pay less. Patients get stuck with different copays depending on their plan, even if they’re getting the same drug. That confusion makes doctors hesitant to switch.

And then there’s the learning curve. A 2022 survey of 217 cancer centers found that 68% had billing confusion during the 2018 code switch. Forty-two percent had claims denied because they used the wrong HCPCS code. That’s not just a coding error-it’s lost revenue and delayed care.

What Works for Providers: Real-World Billing Tips

Practices that handle biosimilar billing well have systems in place. They don’t rely on memory or outdated CMS PDFs. Here’s what works:

- Use CMS’s quarterly drug pricing files-updated every April, July, October, and January. Outdated codes cause 22% of denials.

- Double-check the administered product against the HCPCS code before submitting. Pharmacy staff should verify with billing before the claim goes out.

- For infliximab products, track vial usage. If you use the whole vial, add JZ. If you discard any, don’t.

- Keep manufacturer guides handy. Fresenius Kabi’s 2023 coding guide for STIMUFEND® was rated helpful by 87% of providers who used it.

- Train your billing team for 40-60 hours during any major policy shift. Don’t assume they know the rules.

One clinic in Minnesota cut their claim denial rate from 14% to 2.5% in six months by implementing a dual-verification step: pharmacist confirms drug, billing clerk confirms code. That’s the kind of small change that saves money and reduces stress.

The Big Question: Will the System Change?

Experts agree: the current system works for tracking, but not for driving adoption. The 6% add-on tied to the reference product’s price is the biggest barrier. If you paid biosimilars 106% of their own ASP, providers would have a real financial reason to switch. Avalere Health estimates that change alone could boost biosimilar use by 15-20 percentage points.

MedPAC has proposed a “consolidated billing” model: pay 106% of the volume-weighted average price of all drugs in the class. That’s how many European countries do it. It’s called least costly alternative (LCA) pricing. If three biosimilars are on the market, you pay the average price, and everyone gets the same reimbursement. That rewards competition, not pricing power.

CMS is considering changes. In February 2023, they asked for public input on alternatives to the current add-on structure. A fixed-dollar add-on (say, $120 per dose) or eliminating the reference product’s ASP from the calculation are both under review. If changes come, they’ll likely roll out in 2025.

For now, the system is stuck in the middle. It allows biosimilars to enter the market, but doesn’t give providers a strong reason to choose them. Until the payment structure changes, the U.S. will keep lagging behind Europe-not because of science, but because of billing.

What’s Next for Biosimilar Billing?

The market is growing fast. Biosimilar sales hit $12.3 billion in 2022 and are expected to reach $25 billion by 2027. But growth depends on policy. If CMS sticks with the current model, adoption will plateau around 40-45%. If they adopt LCA pricing or change the add-on, it could jump to 65-70%.

Manufacturers are already adapting. They time their product launches to match CMS’s quarterly payment updates. They build detailed billing guides. They train providers. But none of that matters if the payment system still rewards the most expensive option.

The real question isn’t whether biosimilars work-they do. The question is whether the system will ever stop paying providers more to use the older, pricier drug. Until then, billing complexity will stay high, adoption will stay low, and patients will pay more than they should.

Do biosimilars use the same HCPCS code as the reference biologic?

No. Since January 2018, each FDA-approved biosimilar has its own unique HCPCS code-either a temporary Q-code or permanent J-code. The reference product keeps its own separate code. For example, Remicade uses J1745, while Inflectra uses J3247. This change was made to track each biosimilar’s usage and payment accurately.

How is Medicare Part B payment calculated for biosimilars?

Medicare pays 100% of the biosimilar’s own Average Selling Price (ASP), plus a 6% add-on based on the reference product’s ASP. For example, if the biosimilar costs $2,000 and the reference drug costs $2,500, the provider gets $2,000 + $150 (6% of $2,500) = $2,150 per dose. This means the provider earns more when using the higher-priced reference drug.

What is the JZ modifier, and when do I use it?

The JZ modifier is required on claims for infliximab and its biosimilars when no drug is discarded after preparation. If you use the entire vial, add JZ. If you throw away even a small amount, do not use JZ. This rule went into effect on July 1, 2023, and was introduced to prevent overpayment for unused drug. Incorrect use of JZ is a leading cause of claim denials.

Why don’t providers switch to cheaper biosimilars if they’re less expensive?

Because the 6% add-on is based on the reference product’s price, not the biosimilar’s. A provider earns more per dose by using the brand-name drug-even if the biosimilar costs 20% less. For example, on a $500 difference, the provider makes $30 more per dose with the reference drug. That financial incentive keeps many providers from switching, even when biosimilars are clinically equivalent.

Are biosimilar reimbursement rules the same for Medicare Advantage and private insurers?

No. Medicare Part B pays 106% of ASP. Medicare Advantage plans typically pay 100-103% of ASP, and private insurers vary widely-some pay full ASP, others pay less. This inconsistency makes it harder for providers to standardize billing and for patients to predict costs. A patient might pay $50 for a biosimilar under Medicare Part B but $120 under their Medicare Advantage plan, even though the drug is the same.

What’s the biggest mistake providers make with biosimilar billing?

Using outdated HCPCS codes. CMS updates drug pricing and codes quarterly, and many providers still use codes from the previous year. This causes 22% of initial claim denials. The second biggest mistake is misapplying the JZ modifier for infliximab products. Always verify the administered product and the correct code before submitting claims.

Ryan Pagan

January 29, 2026 AT 13:47Let’s be real - this whole 6% add-on based on the reference drug is a joke. It’s like paying a mechanic more to fix your car with the $200 part instead of the $150 part that works just as well. Providers aren’t stubborn - they’re rational. If you want biosimilars to win, stop rewarding them for staying loyal to the expensive brand. Fix the incentive, not the paperwork.

Kristie Horst

January 30, 2026 AT 08:18Oh, so we’re now rewarding providers for choosing the more expensive option - brilliant. I’m sure the patients who pay 40% coinsurance are just thrilled about this elegant economic design. /s

Paul Adler

January 31, 2026 AT 05:55The JZ modifier is a nightmare. I’ve seen clinics spend hours training staff only to have claims denied because someone forgot to check if the vial was fully used. It’s not that the rule is bad - it’s just poorly implemented. A simple checkbox in the EHR would’ve saved millions in administrative waste.

paul walker

February 1, 2026 AT 12:08Guys. I just learned about this JZ thing and it’s wild. We had a patient cry because their copay went up after we switched to a biosimilar. Turns out, the billing team used the wrong code. I’m not a coder, but this is insane. We need better training. Like, yesterday.

Megan Brooks

February 1, 2026 AT 16:03It’s ironic that the system was designed to increase transparency, yet it’s created more confusion than clarity. The fragmentation of HCPCS codes was necessary, but without aligning reimbursement incentives, we’ve just built a more complicated maze. The real innovation needed isn’t in coding - it’s in payment structure.

Doug Gray

February 3, 2026 AT 11:57So... the system is designed to disincentivize cost-saving measures? Fascinating. The market doesn’t work here because the market isn’t allowed to work. We’ve created a regulatory paradox where efficiency is punished. I’m not even mad - I’m just disappointed. 😔

LOUIS YOUANES

February 3, 2026 AT 18:26Wow. So we pay doctors more to use the expensive drug? That’s not a policy. That’s a corporate subsidy dressed up as healthcare. I mean, if you wanted to keep prices high, you couldn’t have designed it better. Congrats, CMS. You’ve mastered the art of inefficiency.

Andy Steenberge

February 3, 2026 AT 20:22One clinic in Minnesota cut denials from 14% to 2.5% with a simple dual-verification step. That’s it. No fancy software. No new legislation. Just two people double-checking. Why isn’t this standard everywhere? Because we’d rather spend $2 million on EHR upgrades than $20K on training. We’ve lost our way.

Laia Freeman

February 4, 2026 AT 20:35ok so i just found out we’ve been using the wrong code for 8 months?? 😭 like… we lost 12k?? and now the billing person is crying and i dont even know what jz means?? plz send help. also why does every drug have 3 codes??

rajaneesh s rajan

February 5, 2026 AT 22:49In India, biosimilars are 80% cheaper and covered under public insurance. No JZ modifier. No blended codes. Just pay the lowest price and move on. We don’t need 12-page billing guides to give people medicine. Maybe the U.S. needs less bureaucracy and more common sense.

Alex Flores Gomez

February 6, 2026 AT 12:34Let me get this straight - we’re paying more to use the brand name? And the only reason biosimilars aren’t taking over is because the system is rigged? This isn’t healthcare. This is Wall Street with stethoscopes. 🤡

Frank Declemij

February 6, 2026 AT 19:59Fix the add-on. Pay 106% of the biosimilar’s ASP. Done. Everything else is noise.

DHARMAN CHELLANI

February 7, 2026 AT 18:53Biosimilars are just generic drugs with a fancy name. If you can’t handle the coding, don’t prescribe them. Stop blaming the system. Blame the incompetence.

Robin Keith

February 9, 2026 AT 12:54Think about it - this isn’t just about billing codes or Medicare add-ons - it’s about the very soul of healthcare capitalism. We’ve created a system where the act of saving money is punished, where efficiency is anathema to profit, where compassion is buried under layers of administrative Kafkaesque absurdity - and we wonder why patients are disillusioned? We don’t just reward the expensive - we sanctify it. We turn pharmaceutical monopolies into moral institutions. And then we wonder why the system is broken? It’s not broken - it’s working exactly as intended. For someone.

kabir das

February 11, 2026 AT 06:36Can we PLEASE fix this?! I’ve spent 3 weekends re-coding claims because of JZ. My kids haven’t seen me in months. My cat hates me. I’m not even getting paid overtime. This is torture. Someone please tell CMS to just… stop.