When a generic drug hits the shelf, you assume it works just like the brand-name version. But here’s the thing: most bioequivalence studies used to be done on young, healthy men. That’s not just outdated-it’s risky. If you’re a woman over 60 taking a blood thinner or a thyroid med, your body may process that drug differently than the 25-year-old male volunteer who helped approve it. And regulators are finally catching on.

Why Bioequivalence Studies Used to Ignore Women and Older Adults

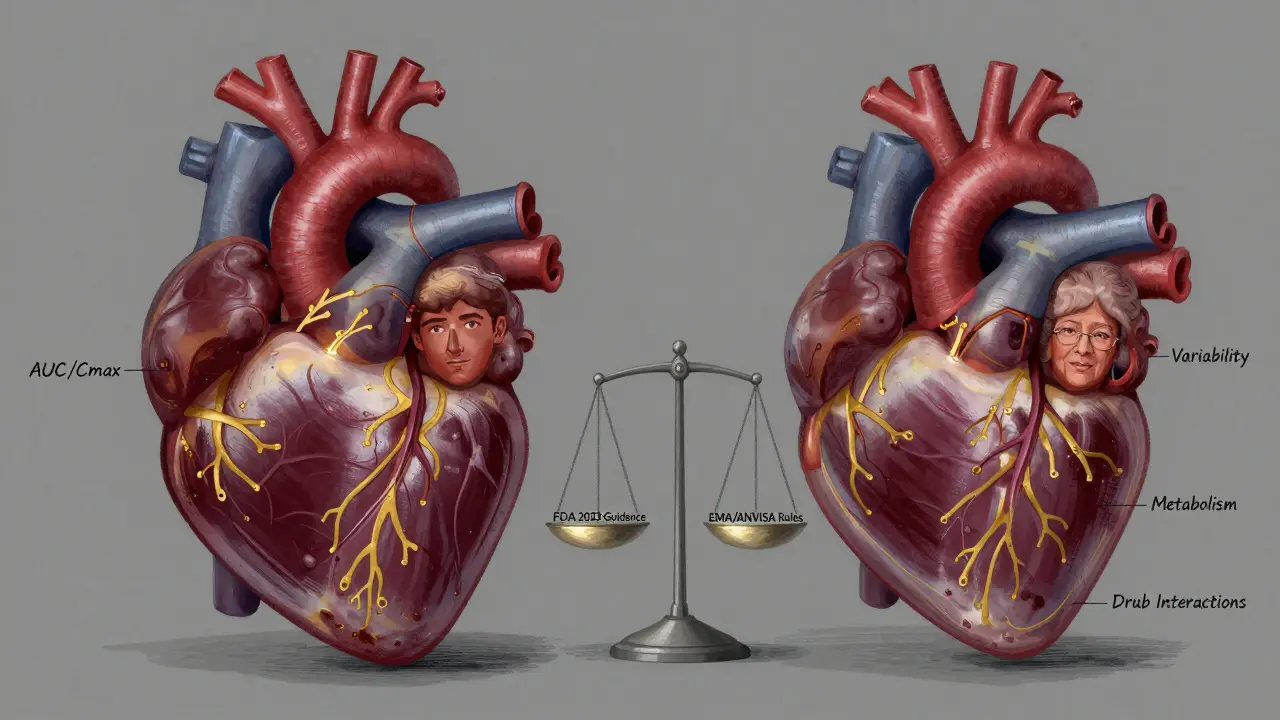

For decades, bioequivalence (BE) studies relied on a simple model: healthy young men, aged 18 to 30, fasted overnight, given two versions of the same drug, and monitored for how fast and how much of the active ingredient entered their bloodstream. The logic? Each person acts as their own control. Simple. Clean. Easy to analyze. But here’s what got left out: women. Older adults. People with real-world health conditions. The FDA didn’t formally address sex-based differences until 2013, and even then, it was just a suggestion. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) said subjects “could belong to either sex”-no requirement for balance. ANVISA in Brazil set strict age limits: 18 to 50. But no one asked: what if the drug is mostly used by women over 65? Turns out, sex and age matter. A lot.How Sex Affects Drug Absorption and Metabolism

Women and men don’t just differ in body size. Their stomachs empty slower. Their liver enzymes work differently. Their fat-to-muscle ratios vary. All of this changes how drugs move through the body. Take levothyroxine, a thyroid hormone used by millions. Nearly two-thirds of users are women. But in BE studies for this drug, women made up less than 25% of participants. That’s not just a gap-it’s a blind spot. A 2023 University of Toronto study found that 37% of commonly tested drugs clear faster in men. For some, the difference was 15-22%. That’s not noise. That’s clinically meaningful. In one study, a generic version of a blood pressure drug showed a 79% point estimate of bioavailability in men but 95% in women. At first glance, it looked like the generic failed in men. But when the same study was repeated with 36 participants instead of 14, the difference vanished. Small sample sizes? They amplify noise. And when you only test men, you might miss how the drug behaves in women entirely.Age Isn’t Just a Number-It’s a Pharmacokinetic Factor

Your body changes as you age. Kidney function drops. Liver metabolism slows. Stomach acid decreases. Blood flow to tissues changes. All of this affects how drugs are absorbed, distributed, and eliminated. The FDA now requires that if a drug is meant for older adults-say, a statin for cholesterol or a diuretic for heart failure-BE studies must include people aged 60 or older. Or, if they don’t, the sponsor must explain why. That’s new. Before 2023, it was common to exclude anyone over 55, assuming “healthy volunteers” meant young. But here’s the problem: older adults often take multiple drugs. A BE study done on a 28-year-old who only takes one pill a day doesn’t tell you how the generic will interact with five others in a 72-year-old. The EMA and ANVISA still mostly require healthy volunteers without chronic conditions. The FDA allows people with stable conditions-like controlled hypertension or diabetes-if those don’t interfere with the study. That’s a big shift.

Regulatory Differences Around the World

Not all agencies see this the same way. The FDA’s 2023 draft guidance is the strictest: if the drug is used by both sexes, you need roughly equal numbers of men and women. No exceptions unless you have strong data to justify it. They also want to see age diversity: if the drug targets seniors, you need seniors in the trial. The EMA? Still says “subjects could belong to either sex.” No quota. No requirement for balance. They care more about detecting differences between formulations than reflecting real-world use. ANVISA in Brazil demands equal male-female distribution and strict age limits: 18 to 50. No one over 50. No one under 18. No smokers. No one with BMI outside ±15% of normal. It’s rigid. But it’s clear. Health Canada sits in the middle: 18 to 55, with no formal sex ratio requirement. This patchwork creates headaches for drug makers. A company running a global study has to design one protocol that satisfies all of them. That’s expensive. And slow.The Real Cost of Not Including Women and Older Adults

It’s not just about fairness. It’s about safety. When women are underrepresented in BE studies, we don’t know if they’ll get too much or too little of the drug. Too little? The drug doesn’t work. Too much? Side effects pile up. For drugs with narrow therapeutic windows-like warfarin, digoxin, or lithium-that’s dangerous. A 2021 FDA analysis of 1,200 generic drug applications found that only 38% had female participation between 40% and 60%. The median? Just 32%. Meanwhile, for drugs like levothyroxine, antidepressants, or osteoporosis meds, women make up 60% or more of users. That mismatch isn’t accidental. It’s structural. Recruiting women is harder. Sites report 40% longer enrollment times. Women juggle caregiving, work, and family. Clinical trials often run during business hours. They don’t offer childcare. They don’t adjust schedules. And until recently, there was no regulatory push to fix it. Now, the FDA is watching. If you submit a BE study with 20% women for a drug used mostly by women, expect questions. Justifications. More data. Delays.

What’s Changing-and What Still Needs to Change

The tide is turning. In 2022, 68% of contract research organizations (CROs) started actively recruiting women. Some are offering evening appointments. Some are partnering with women’s health clinics. Some are tracking sex-specific pharmacokinetic data-not just the average, but how men and women respond separately. But only 29% of those CROs routinely analyze results by sex. That’s a problem. You can’t just enroll more women-you have to look at the data differently. The FDA now requires sponsors to pre-specify subgroup analyses for sex and age. That means: before the study even starts, you say, “We’ll look at men and women separately.” No fishing after the fact. No cherry-picking results. Still, there’s no standard way to define “bioequivalence by sex.” Should we use the same 80-125% confidence interval? Or should we tighten it for drugs where sex differences matter? The National Academies of Sciences suggested that in 2021-but regulators haven’t acted yet. And pediatric populations? Almost entirely ignored. The FDA says you can extrapolate adult data to kids-but only if you have strong justification. That’s not enough. Kids aren’t small adults. Their organs develop at different rates. We need dedicated pediatric BE studies.What Sponsors and Researchers Should Do Now

If you’re developing a generic drug, here’s what you need to do:- Match your study population to your target users. If your drug is for postmenopausal women, enroll postmenopausal women. Don’t assume young men are a proxy.

- Plan for sex and age subgroup analysis. Don’t wait until the data comes in. Pre-specify it in your protocol. Use stratified randomization.

- Recruit early and strategically. Partner with community clinics. Offer flexible hours. Include transportation support.

- Document everything. The FDA wants to see why you chose your population. If you excluded older adults, explain why. If you enrolled 80% men, justify it with data.

- Track more than just AUC and Cmax. Look at variability within sex groups. Are women’s responses more spread out? That’s not a flaw-it’s information.

What’s Next?

The EMA is reviewing its 2010 BE guideline. Updates are expected in 2024. Expect them to move closer to the FDA’s position. Other agencies will follow. The goal isn’t to make studies bigger or more expensive. It’s to make them smarter. To stop pretending that a 22-year-old man represents everyone. Because he doesn’t. The future of bioequivalence isn’t about one-size-fits-all. It’s about understanding who’s taking the drug-and making sure the generic works for them, too.Why were bioequivalence studies historically done only on young men?

Early bioequivalence studies used young, healthy men because they were seen as the most predictable population. Their physiology was assumed to be stable, with fewer variables like hormonal cycles, pregnancy, or chronic diseases. This made data easier to interpret and regulatory approval faster. But this approach ignored known biological differences between sexes and age groups, leading to gaps in how drugs perform in real-world users.

Does the FDA now require equal numbers of men and women in bioequivalence studies?

Yes, under the May 2023 draft guidance, the FDA requires that if a drug is intended for both sexes, the study should include similar proportions of males and females-roughly 50:50. Deviations must be scientifically justified. This is a shift from previous guidance, which only recommended balanced enrollment without requiring it.

Are older adults included in bioequivalence studies?

The FDA now requires inclusion of adults aged 60 and older if the drug is intended for elderly populations. If excluded, sponsors must provide a scientific justification. Other agencies like EMA and ANVISA still primarily require healthy volunteers aged 18-50 or 18-55, with less emphasis on older adults.

Why is sex-specific data analysis important in bioequivalence?

Sex differences can significantly affect how drugs are absorbed, metabolized, and cleared. Small studies with few participants can produce misleading results-like apparent bioinequivalence in one sex that disappears in larger trials. Pre-specifying sex-based analysis ensures that differences aren’t dismissed as noise and helps identify real safety or efficacy concerns.

What are the biggest challenges in recruiting women and older adults for BE studies?

Recruiting women and older adults takes longer and costs more. Women often juggle caregiving responsibilities, making fixed-hour clinical visits difficult. Older adults may have multiple health conditions or mobility issues. Many sites lack flexible scheduling, childcare support, or transportation assistance. Until recently, there was little regulatory pressure to fix this, so few sponsors prioritized it.

How do regulatory agencies differ in their approach to sex and age in BE studies?

The FDA requires balanced sex representation and inclusion of older adults for relevant drugs. The EMA allows flexibility without mandating balance. ANVISA requires equal male-female distribution and strict age limits (18-50). Health Canada accepts 18-55 but doesn’t enforce sex ratios. These differences create complexity for global drug development.

Meghan Hammack

January 10, 2026 AT 11:32This hit home for me. My mom takes levothyroxine and I’ve seen her crash when the generic switched. No one told us why. It’s not just science-it’s survival.

Why do we keep pretending one-size-fits-all works when our bodies are so different?

They tested on 25-year-old guys. My mom’s 72. She’s not a lab rat. She’s a person.

Maggie Noe

January 10, 2026 AT 12:57😮💨 The fact that we’re still arguing about this in 2025 is wild. We’ve sent people to Mars but can’t figure out that women’s livers aren’t men’s livers? 🤦♀️

It’s not bias-it’s biology. And biology doesn’t care about your budget or your convenience.

Gregory Clayton

January 10, 2026 AT 21:35Ugh. Another woke study. Next they’ll say we need to test on cats and dogs too. Young men are the standard because they’re consistent. You want diversity? Go to a pharmacy and buy the brand name. Problem solved.

Stop making medicine a political trophy.

Alicia Hasö

January 12, 2026 AT 06:21To everyone who says this is ‘overcomplicating’ science: You’re right. It’s not complicated. It’s just honest.

We don’t test heart meds on toddlers. We don’t test baby formula on octogenarians. So why do we test thyroid meds on 22-year-old men?

This isn’t activism. It’s basic pharmacology. And if you’re mad about it, maybe you’re mad because you’ve never had to take a pill that might not work-or might kill you-because of a study that didn’t include you.

Johanna Baxter

January 14, 2026 AT 05:32They knew. They always knew. And they didn’t care. Women’s bodies were always the afterthought. The cost? Our lives.

My aunt died from a generic blood thinner because they never tested it on women over 60. No one even apologized.

It’s not a gap. It’s a grave.

Jerian Lewis

January 14, 2026 AT 09:19There’s a reason why most BE studies exclude older adults. It’s not malice. It’s logistics. Chronic conditions = noise. Noise = harder to prove equivalence.

But yeah, we’re ignoring the people who actually need the drug. That’s… not great.

Kiruthiga Udayakumar

January 15, 2026 AT 18:20India has 200 million women over 50. Most take generics. But our regulators still use 18-50 guidelines. What are we supposed to do? Guess?

Our moms are dying because someone in a lab coat thought young men were ‘cleaner data.’

This isn’t science. It’s negligence.

Patty Walters

January 16, 2026 AT 18:01Wait, so if I’m a 68-year-old woman on warfarin, and the generic was tested on 14 dudes, and my dose is off by 10%… that’s not a ‘risk,’ that’s a waiting game for a bleed.

Also, why do we call them ‘healthy volunteers’? I’ve never met a 25-year-old who’s ‘healthy’ and takes 5 meds. We’re just lying to ourselves.

Ian Long

January 18, 2026 AT 05:51I get the frustration. But let’s not throw the baby out with the bathwater.

Yes, we need better data. But if we start requiring 100 participants per subgroup, studies will cost $5M. Generics will disappear. Prices will skyrocket.

Maybe we need tiered approaches: simple studies for low-risk drugs, deeper ones for narrow-window meds. Not all drugs are warfarin.

Angela Stanton

January 19, 2026 AT 19:11Let’s break this down statistically. The 80-125% CI is built on young male PK. When you introduce sex dimorphism, the variance widens. You’re not just testing equivalence-you’re testing *overlap*.

But no one’s modeling the posterior predictive distributions by sex. Until we do, we’re just running blind trials with bigger sample sizes. More data ≠ better science if the model’s wrong.

Ashley Kronenwetter

January 20, 2026 AT 13:24The FDA’s 2023 guidance is a milestone. But implementation is inconsistent. Many CROs still treat sex as a demographic checkbox, not a biological variable.

Pre-specifying subgroup analysis is necessary but insufficient. We need standardized reporting templates. And we need to publish negative results. The silence is killing people.

Heather Wilson

January 21, 2026 AT 22:18Here’s the real problem: no one tracks adverse events by sex in post-market surveillance. So even if a generic ‘passes’ BE, we won’t know if it’s causing more strokes in women until someone dies.

Regulators are playing catch-up. And patients are the lab rats.

Lindsey Wellmann

January 23, 2026 AT 02:10Imagine if car safety tests only used 25-year-old male crash dummies. Would you drive that car?

Yet we do this with medicine every day.

It’s not just unethical. It’s terrifying. 🚨💔

Pooja Kumari

January 23, 2026 AT 18:57Look, I get it. We need to include older women. But let’s be real-recruiting them is a nightmare. They have appointments. They’re tired. Their kids won’t drive them. The clinics are in corporate parks, not neighborhoods.

And then you pay them $50 for 8 hours? That’s insulting. We need to treat this like a public health crisis, not a regulatory checkbox.

Also, why don’t we just test on real patients instead of ‘healthy volunteers’? We’re not testing magic pills-we’re testing life-saving tools. Let’s test them on the people who need them.